Marble kouros (c.590-80 BCE).

For young men, all things are as they should be when they are in the brilliant flowering of their youth, an object of admiration for men and desire for women, and beautiful in death in the front rank.

Tyrtaeus, ‘Fragment 7’

It is one of the wonders of the world. You round a corner from the Met’s entrance hall and see the sculpture deep in a room to come, framed in a tall narrow door. There are windows opening onto Fifth Avenue. Light hits the sculpture from the left – light from the east, strong and steady. And always, whether it’s years or days since the last time I stood here, it is the colour of the stone that takes me by surprise. Surely before it wasn’t this pink! And what an inadequate word! The stone isn’t flesh-coloured or rosy-fingered, it isn’t male or female, it isn’t flushed with blood. Maybe, on the plaited hair and immaculate eyelids, it looks a little ‘made up’. It is stone partaking of life.

They say that statues like this originally had paint applied to them. I believe it; but the mind reels at the thought of what the painter could have been called on to do. The colour of the stone – the nakedness of the stone, the play between fleshiness and stoniness – was everything. Of course, the painter knew this. (I leave to one side the absurdities practised on the public in recent decades by archaeologists excited by the idea of Greek temples and statues blazing with reds and blues. Apollo in rouge, Venus in furs, the Panathenaea ambling by like dobbins on a carousel. We do have examples of Greek painting, these painters seem to forget, in the tombs at Paestum, at Vergina, on white-figure vases.)

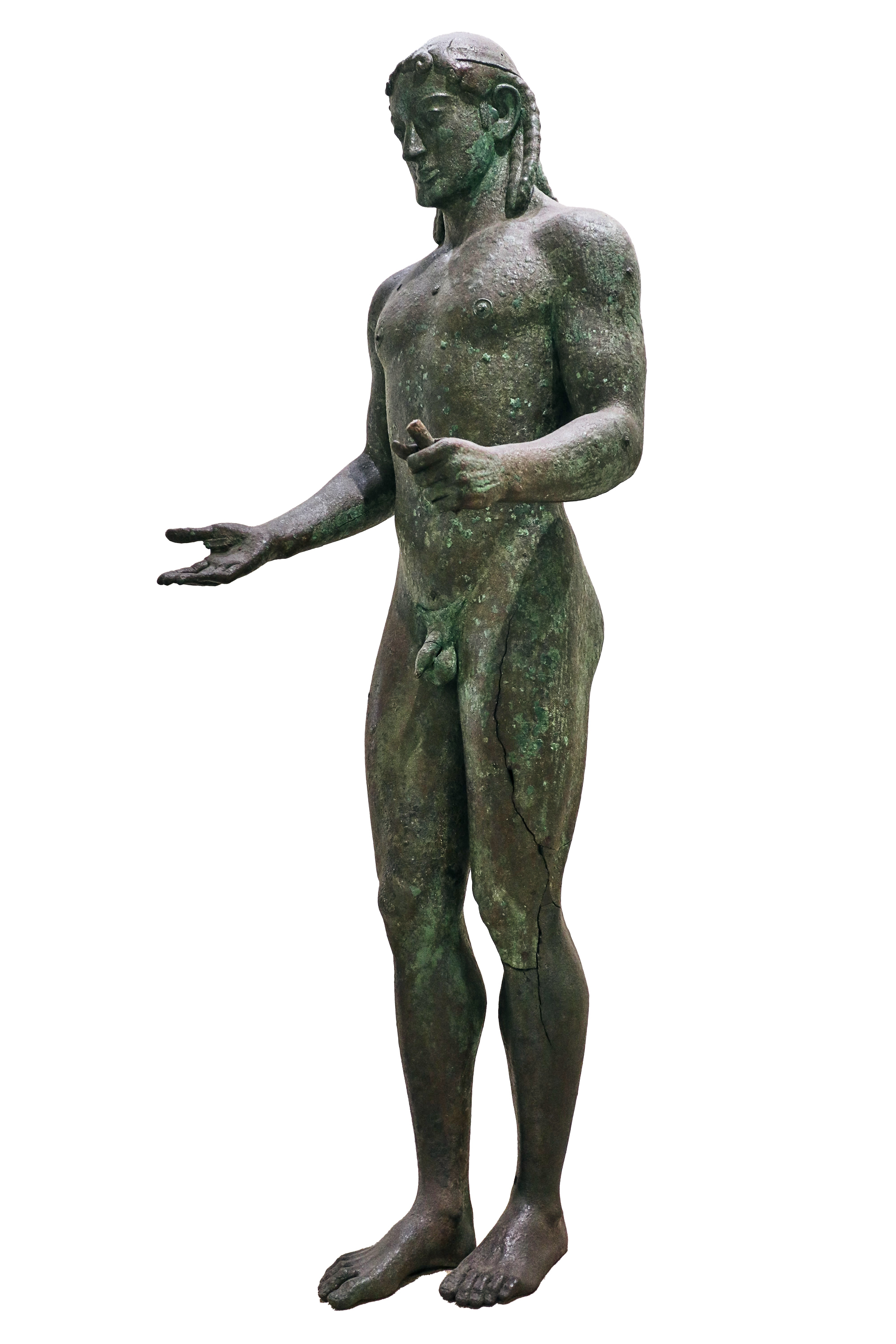

There were, no doubt, workshop traditions in the period – habits of transparency and guides to just sufficient emphasis in paint – that are utterly lost to us, and which surviving paint traces can only hint at. There must have been skills – subtleties, certainties, observations, abstractions – meant to equal those that survive in the stone. We respond to what we have left. To call the figure in the Met a kouros is to adopt a term for the sculptural type (Greek for ‘young man’) that the ancients never used in the same way. They took the type for granted: it was everywhere in their world of representation. ‘Like to a man, lusty and powerful, in his first bloom, his hair spread over his broad shoulders,’ as a Hymn to Apollo has it. A naked man – the lack of clothing is essential and new, and seems to have derived from an emerging culture of homosociality – is shown standing tall, striding forward, weight evenly balanced, arms by his side but held in slight tension, fists wrapped tight around a remaining nub of stone. The man might be a famous athlete, or a fallen warrior, or a god.

‘Nakedness in all its strength’ is a verdict on the Met sculpture I remember. It struck me as a good beginning, and stays in the mind, but immediately (repeatedly) one realises there are other fundamentals to the sculpture that make ‘strength’ seem too pat as a summing up. The figure’s smallness, for instance. Its proportions: the size of its head in relation to its torso and waist. The length – the restraint – of its stride. Nonetheless, there is something in the young man’s presentation of his body (his chest, shoulders, abs) that speaks to hardness and training, not to say pride, poise, self-confidence, self-evidence, shamelessness, maybe even a steady (Nietzschean) provocativeness. And this, too, like the stone’s pink, is a quality in the figure – an overall character – that seizes you as you look, breaking through your defences. Other onlookers, coming into the gallery, seem to experience the same shock.

I’ve never been in the room at the Met for long without a ripple of laughter filling the space. The laughter often comes from a group of youngsters, female and male; it’s usually soft and a bit condescending, but you sense that they are genuinely nonplussed. The titters soon die out. But they are there, time and again, as a first, seemingly necessary, apprehension. The group sees the sculpture and sees what the sculpture wishes them to see.

I suppose what has viewers giggling is that the body revolves round its genitals. Never have genitals been so exposed. Size doesn’t matter. Never has a body been so uncomplicatedly anchored to a single (threefold) masculine fact. The man’s chest and shoulders are the fact abstracted. The rope lines of the groin attach the abstraction – just – to the body. The two hands, soldered to the thighs with a bridge of rough stone, seem needed to hold the essential extraneity in place.

So, the question of the Greeks and the masculine presents itself. The Greeks and power, the Greeks and patriarchy. In order to put the question properly, or at least to defer for a moment the (condescending) answer built into most forms of the question, I would like to enter as companion to the Met kouros a set of feminine faces dating from much the same time.

Clay masks from the temple of Artemis Ortheia, Sparta (seventh to sixth century BCE).

They are masks found in the temple precincts of Artemis Ortheia at Sparta. It is impossible to date them securely, but they must have been made in the sixth or seventh century BCE. The Met kouros comes from the early years of the sixth century: 590-580 is the consensus. It is Attic (its exact place of discovery isn’t known); the cult of Artemis, however, though firmly part of Greek religion everywhere, seems to have taken a special, perhaps peculiar, form in Sparta. Faces such as those found in the precinct are sometimes called Phoenician, but wherever they came from they were soon being made on site, in quantity. The masks were probably worn by young men as part of what we now uneasily call an initiation rite. (Parallels with present-day ‘tribal’ societies are seized on with less confidence than in the days of Nuer Religion.)

The masks from Sparta are grotesque, presumably meant to be comic. It is by no means indisputable that the faces are female, though they are certainly aged, wrinkled, gap-toothed. If the masks were instruments in the passage from boyhood to manhood, perhaps the youths putting them on thought they were adopting for a moment the infirmities of old age. Ageing can blur the lines of sexual difference – this may have been part of the comedy – but I have to say that these masks (and others like them from Sparta) look female to me. Maybe in the rite physical decrepitude and being old-womanish went together. And this possibility is all the more challenging, interpretively, if one recalls that the god superintending the revels was Artemis, god of female mystery/mastery, mistress of the animals, guardian of chastity, leader of the hunt. Her worshippers revered and feared her. The young men at Sparta were whipped as they danced. Blood flowed over the altar.

Kore discovered in Keratea (570 BCE).

Artemis was also the goddess of the pains and dangers of childbirth, to be placated particularly as childbed drew near. Women, so the cult of Artemis affirmed, are the ultimate owners and tamers of the body – of the body’s essential (maybe only) power, which is to reproduce itself. But for that very reason women are dangerous: to men, who will never stop resenting the fact that their power over women’s bodies is the power, ultimately, of a handmaid to the perpetuation of the species; and to themselves. Here are the roots of misogyny.

The masks’ grotesqueness needs to be supplemented, it follows, by images of Artemis’ cruelty and authority. And also her loveliness. I need, beside the toothless crones, a figure of female self-sufficiency to put beside the Met kouros. What matters is conceptual and aesthetic dignity: for the moment, style and chronology cede to them. There is a funeral marble of a woman, found in Attica, most probably sculpted twenty or thirty years earlier than the kouros, that is in some ways a match.

Artemis of Piraeus (fourth century BCE).

The woman is an aristocrat, dressed as Hades’ bride in pleated red robe, folds immaculate as the fluting on a column, platform sandals, deathly pomegranate in one fist, expression studied yet complaisant, hair crimped for eternity, crown carved with procreant lotus buds. She is magnificent, but in the end too provincial – too pompous. To have her be the kouros’s companion would play into a male-female contrast of naked versus clothed, actor versus icon, self-moving versus ‘statuesque’. Artemis, like the woman kitted out for the underworld, is a god who stands tall – her epithet in Sparta was Ortheia, upright – but she is also dangerously mobile, urging her hounds to the quarry. She turns an implacable gaze on her worshippers. The representation of her that seems to me to gather all these threads – to stand opposite the Met figure as Greek culture’s most complete image of the feminine – is a bronze from the second half of the fourth century BCE, now preserved in the museum at Piraeus.

The bronze in Piraeus is late, of course: an achievement from the period just before the decline of Greek classicism, as opposed to the kouros at its beginning. If we rid the terms here of their evolutionary baggage – ‘stammering stiffness’ leading to ‘progress in naturalism’ to ‘classical synthesis’ to ‘eventual decline’ – they seem to me still usable as crude markers. Ends and beginnings are often in dialogue. The reaching out and easy balancing of the Piraeus Artemis is for me the necessary matrix against which to measure the Met statue’s compactness and restraint. The figure in the Piraeus Museum even has a companion in a bronze archaic Apollo a few yards away, part of a group of five statues discovered in the port city in 1959, stored for shipment long ago, or maybe just hidden together in a time of war. (I call the Apollo archaic, though many academics think, and I can see why, that the sculpture is an archaising imitation of an already distant past.) Were the two bronzes, of the twins Apollo and Artemis, perhaps made to be compared, almost in the way I am trying to?

Clay figure of a woman excavated at Brauron.

I believe, to put it plainly, that an ‘archaic’ kouros and a fourth-century bce Artemis are figures that the Greeks themselves may have thought of as belonging together – in opposition. All the same, chronology can’t be abandoned. I need, as a further point of reference, at least one sculpture of a female figure made at roughly the same time as the male in the Met. It’s not easy: there is a gap in the surviving sequence of stone maidens. The Louvre’s mysterious Dame d’Auxerre – mysterious because lacking a provenance – seems to have been made thirty or forty years earlier, perhaps in Crete. The great series of kore found on (or associated with) the Acropolis belongs to the mid-sixth century and later. In the end, I prefer the smaller women made in clay, probably in the late seventh century bce, no doubt as votive offerings, that were excavated from the sanctuary at Brauron, the great site of the Artemis cult in Attica. The young daughters of the Athens elite went there before puberty to ‘act the bear’ for the goddess – becoming wild animals in Artemis’ train, to be tamed or subdued by her. The precinct, with its wild rockscape and glimpse of the sea (not to say its associations with the murder of Iphigeneia) still makes one’s hair stand on end. No one is sure who the clay women from the site were meant to be. Most probably Artemis herself – elaborately robed and hatted (or is it coiffed?), the tilt of her head maybe protective (some votives from the same site show her, or a figure that could be her, as a mother suckling a child), her expression impenetrable.

The kouros, then, has many consorts. All the figures just mentioned are informative, though only the bronze in Piraeus strikes me as fully capable of answering back to (living up to?) the Met statue’s male uprightness. Strong enough, we might say, to speak back to the kouros’s deep knowledge of, and affinity for, the sculpture of Egypt.

Egypt is a good starting point for the Met figure; but one that has to be cleared straightaway of cliché. Egyptian sculpture – look again – is not stiff. It is not stereotyped and hieratic; or not if these adjectives are meant pejoratively. Bodies made by the best Egyptian sculptors strike a unique balance between composure – art historians used to call it ‘arrest’, but we might prefer ‘respect for a stone replica’s essential stillness, its stopping of the flow of time’ – and intimation of movement. The ways these craftsmen found to intimate stress, self-control and high tension within a stone body have never been rivalled. The Greeks knew this well. However the sculptor of the Met kouros, for example, may have conceived his figure’s relation to Egyptian precedent – with a mixture of admiration and rivalry, by the look of it – he would surely have laughed at the notion that his sculpture was shaking off Amenemhat’s rigidity. Amenemhat’s what? If only something approximating the implied pressure of the pharaoh’s spread fingers on his shendyt, and the power of his held breath, and the geometry of his neck and shoulders, could ever be done again!

No doubt the man who made the kouros knew Egyptian art from the inside. His workshop must have been organised around ways of envisaging and calibrating derived from Egyptian practice. But words such as ‘convention’ or ‘canon’, which still dominate writing on this subject, strike me as leading in the wrong direction. What kind of convention could have guided, for example, the slight imbalance – the almost imperceptible downward slope from left to right – in our young man’s collarbone? What did a canon of measurement have to do with the play between the collarbone’s slope and the answering line of the man’s simple necklet? (How exquisite the final twists of leather – is it leather? – holding the necklet in place.)

Piraeus Apollo (fifth to fourth century BCE).

The sculptor who did such things certainly existed, securely, unquestioningly, within an idiom, and had at his disposal a repertoire of established techniques; he had a set of bodily proportions at his fingertips; but he knew full well that in the kouros he was using such knowledge to unique – I am sure, unprecedented – ends. Look at the length and depth of the declivity between the young man’s breasts, and its continuation down to his navel! It is one key to the figure’s self-holding, making it clear (palpable) that the body’s uprightness is something achieved, held under tension, not settled for all time. The depth and modulation of the line is entirely the sculptor’s invention – his balancing of abstraction and anatomical fact. No one had struck the balance in this way before; nor had anyone made a neck of just this narrowness and tensile strength, with the necklet twisted to spell out its pure geometry; nor made a thigh come forward at just this lever angle from the buttocks; nor a ribcage ending in such a faint inherent shadow line, as if following a vein in the marble.

Marble kouros detail.

Existing within an idiom. Being entirely at ease with Egypt, which surely meant being in proper awe of it. Stone, the Egyptians thought, or at least the kinds of stone they chose for jobs that mattered most, remained what it was for ages to come: it was the stuff of endurance. But if it was to be a likeness of a human body, the qualities of hardness and softness, of invulnerability and mortality (many kouroi, almost certainly including the one in the Met, commemorated a fallen warrior), both had to be present. To be visible and touchable. The two dimensions to existence – the time of the sun god, eternal and indestructible, and the human ‘lifetime’, already over – had to co-exist, not commingle. Some viewers of the Met kouros talk of its anatomy being drawn on the stone. Well, yes – in the way that any great draughtsman, be it in Middle Kingdom Memphis or High Renaissance Rome, finds the means to make a line embody a substance and texture, or the curve of an entity in space, without the line for an instant pretending to be anything other than a mark dragged or incised on a plane.

Take the line depicting the kouros’s ribcage. Follow its curve, try to imagine the tempo of its making and the decision to stop. Surely it wasn’t the case that the sculptor finally refrained, as a result of technical limitations, or out of some aesthetic-political puritanism, from too much emphasis on the ribs, too much illusionism, too much individuation. ‘Truth to materials’ went without saying. The sculptor’s task was embodiment, animation. The stone, and the idiom of working he had mastered, divulged the exact holding of muscle and breath. The reality happened under the punch. Sufficiently. Definitively.

There is a danger here, I know – in this pointing at the sculptor’s decisiveness and subtlety – that the kouros in the Met will come to seem all certainty, all luxuriating within an idiom. But this is as bad as ‘stammering stiffness’. The kouros is inaugural, meaning experimental: it is testing the implications (the possibilities) of its inherited types and techniques – testing them relentlessly, to the point of silent, almost sly, contradiction. You move from front to back and you’re confronted by a different figure. Look at the two segments of circles standing for shoulder blades. Compare them with the tracing (the degree of abstraction) of ribcage, breast and clavicle on the figure’s front. Look at the bowed line marking the haunches – the top of his buttocks. Compare the three dimensions of the groin. Look at the way the whole outline of the kouros’s shoulders, back and buttocks chimes with the regular curves (again, the degree of abstraction) of the incised shoulder blades. Look at the way the carving of the elbows responds to the line of the haunches.

Do the front and back of the figure inhabit two different worlds? Or is the feeling of difference – even contradiction – here the product of our ‘stereotyped’ expectation of the way a body, or a sculpture of one, should cohere? Or of an unthinking assumption about what counts as consistency within an idiom? Which consistency is it, anyway? Of technique or of attention? Or are we agreeing to take the former as the mark of the latter? A young warrior’s backside isn’t worth looking at in the same way as his breast or biceps? Is that it?

Marble kouros back view.

Are the kouros’s elbows, and the sinews of his lower arm, seen from the back, attended to? It seems so to me – fiercely, brilliantly; but clearly the result has been registered on the stone in a very different way from, say, the shadow line of the ribcage. What is consistency, anyway? Is consistency true to life? Don’t human bodies, as a result of evolution, possess ‘faces’, fronts and backs, foci, modes of address, kinds of invitation to attention alongside accidental, not-to-be-looked-at mechanics? Elbows, with the skin unstretched from the bent elbow (spear-throwing) position, are not to be looked at. But the kouros sculptor has looked with a vengeance, with ironic delight. And the not-to-be-looked-at, he has decided, has to be there in the form he gives what he sees. On the kouros’s front, the ribcage (lovely metaphor), groin and sternum are also mechanisms, but they double as attractors, advertisements, signs of power, gender, fitness – evolved as such, or elaborated as such. An elbow … maybe not.

Of course, the sculpture drives the point home. The bending of an arm is one thing, and need not be drawn into the realm of signifying; the survival of bits and pieces of body hair – that’s another! Those tight-balled curls, those plaits, that pattern, that ‘consistency’! They’re telling the story of civilisation. (Could the hair be a wig? There are traces of red paint here and there, but it’s impossible to tell how striking the colour was originally.) Isn’t the sculptor laughing quietly at the change of gear he’s contrived, from a schematism down below meant to approximate attention to one up above that means us to admire, to fixate. (Sometimes human hair is halo, veil, necessary beautification. Imagine the kouros’s face without its frame. Sometimes getting rid of hair is an aesthetic-erotic coup de grâce. Imagine the kouros with pubic hair. Again, I sense the sculptor’s smile here at the rhyming – the inversion – of genitals with head.)

Where does this leave us as regards the young man’s masculinity? Is a wig or a hairdo masculine? ‘These men have come to fight us for the pass’ – Xerxes is baffled by the news that the Spartans at Thermopylae are combing their long hair, and his spy has to explain – ‘it is for this they are preparing. This is their custom: when they are about to risk their lives, they arrange their hair.’ Jean-Pierre Vernant tells us that the very word kouros is connected with keirō, ‘to cut one’s hair’. The Spartan word for hairdressing was xanthizesthai, meaning ‘glossing or glazing with the brilliance of gold’. In the Iliad, Achilles and his friends cut off their hair and strew it over the corpse of Patroklos before putting him on the pyre.

Let’s assume, then, that the sculptor meant his kouros to be beautiful. But did that mean desirable? And if so, by whom? We know already that viewed from the front the figure’s maleness is a touch assertive, certainly shameless, maybe discomfiting. Does that evoke desire? No doubt. But also disorientation. Perhaps the back of the kouros is (and was understood to be) more easily desirable than the front. Does the abstraction of form on the figure’s rear invite a different kind of admiration, or imaginary possession, from the wide-eyed self-holding of the figure moving in our direction? Perhaps. But what kind of admiring? The exquisiteness of the kouros’s hairdo – the precision, the tightness, the relentlessness of repetition – strikes me as derealising the figure it crowns. But that too can be a trigger of desire.

Smaller Artemis of Piraeus (fourth century BCE).

I leave these questions open, and retreat to the figure seen from the front. The two first things I said about it were that its extraordinary colour gave it a kind of life for which the categories ‘stony’ and ‘flesh-like’ seem too glib; and that the body as a whole was tied to the genitals. I worry that the figure brought onstage so far is too uncanny, and too proud of his equipment. Maybe that’s one moment of the kouros’s presentation, but there are others – other aspects to the man and his motion, other ways his dimensions can strike you. I’ve talked too much about front and back. Side views are also beautiful and important, oblique views, views from a distance, views from up close. These views can fuse into a totality at odds with those that seemed reasonable before – not because (I hope) I’m looking for contradiction, but because the elusiveness of a body’s character, and the sculptor’s sensitivity to that elusiveness, simply present themselves. They are the facts this morning.

For instance, a morning in January 2018: an entry in a notebook.

This time, coming in from the door to the north, the kouros is immediately more modest, more reserved, standing to a kind of unemphatic attention as if waiting for instructions or the order to stand at ease. He’s less resplendent, no touch of ostentation to him, so that his genitals today seem less ready for action; his eyes are almost downcast, his necklet touching, his slim waist and faint high rib in tune with the quiet arrest. The slight turning towards us of the inside of the elbows, showing their softness, adds to the unassertive mood. Heavy arms, massive upper arms especially, but held in a way that neutralises their threat. Kneecaps proclaiming the body’s complex mechanical splendour, but also its vulnerability.

Looking at the rhyme between groin and ribcage, and the line going down to the navel, I think of Egypt again. This is the inheritance: this exquisiteness of abstraction, from a nature still palpable in the sign. The same is true (where does one stop?) of the collarbone’s curve in relation to the necklet, or the sharp edges of the shinbones in relation to the breastbone above. Or the eye sockets and patellae!

With the head, yes, we are in a different world. The face shines down at us. All its proportions are bewildering: the scale of each feature, and the degree of attachment of each feature to the head. The balance between overall composure in the face and absolute (deathly) remoteness is not like anything, as I recall, in the line of kouroi to come. Maybe the nearness of Egypt made this possible; but the possibility was not one that Egypt itself cared for. A face in Egypt survives death: its granite or quartzite immobility is the mark of eternity, not mortality, on its features. The kouros’s face defies interpretation: surely that, above all, is what produces the on-and-on escape of the figure from any one understanding (by me) of its stance, its affect, its hold on the world, its staging of its own depiction. The mouth, the nose, the arched eyebrows, the enormous eyes, the long, long neck … Wouldn’t you say they are lordly, circumspect, abstracted, alert, unconscious, alive, indifferent to aliveness, wonderfully generalised, precise to the point of fastidiousness, masked, unmasked, soft-fleshed, hatchet-chinned, adolescent, beyond the grip of time?

Seen from the side, the figure seems to be holding its genitals steady, as if they were a weight needing to be balanced by his buttocks – as if he were holding them in check. (But, as usual, putting this into words pushes the appearance too far: it’s not a tension or an ostentation.)

And one more touch of certainty … Look at the way, from the side, the back of the young man’s neck is outlined against, steadied and protected by, the filled-in space between neck and hair. I don’t give a damn whether the stone wasn’t pierced through out of ‘technical caution’, or as a nod to previous best practice, or whatever. It’s what the sculptor made of the convention that matters. The play of solid and declivity here, contour and shadow, is as fine-tuned as anything on the figure’s breast and abdomen, and once again the body (the neck, the jawbone, the base of the skull) is balanced between strength and fragility.

Artemis of Ephesus (second century BCE).

The bronze Artemis in Piraeus has a partner. In the group of statues found packed together there was a second Artemis figure, sculpted a century or so later: smaller, younger, more battered and encrusted, the set of her arms more clearly implying the holding of a bow. The heads of the two figures are in dialogue. The original state of the younger Artemis’ face is specially touching. (Restoration maybe tips her determination into querulousness.)

Focusing on the fourth-century bce Artemis, but now with her partner as foil … What kind of opposite or complement to the kouros do we take this Artemis to be, remembering that the Piraeus group included a kouros done in the manner of two centuries earlier? What kind of thinking and feeling is being articulated in Artemis’ stance and expression, on and around the categories male and female, life and death, arrest and movement, mortal and immortal? Are these the categories at issue? If so, do they survive their materialisation?

Terracotta antefix with Artemis holding two lions (c.500-480 BCE).

The sculptor’s thinking is complex; it immediately challenges my ability to put an expression or a mode of engagement into words; but surely the thinking is not, in our present terms, ‘enlightened’. Civilisations, sadly, are not to be judged by the measure of their doubts about power and hierarchy, or even by the positive value they may have placed, as descant to subjection, on pity, care, compassion, sympathy, tenderness, amity, fidelity, community; but, rather, on the range and depth of their representations of the human, it being understood that many, maybe most, aspects of that state were confirmed as subordinate exactly by being given convincing form – shown as deviant, dangerous, seductive (of course), weak, ecstatic, aggrieved, delusional, uncontrollable, on the edge of the human. In the Greek case, apropos ‘Women’, the representations included Hera, Athena, Aphrodite and Artemis (Artemis with all her epithets: ortheia, brauronia, iocheaira, laphria, chrysinios, ephesia, lochia, alphaea, limnatis, potnia theron, stymphalia, phosphoros, kalliste, soteira, amarynthia and many more … Artemis leading back, whether in earnest or as part of a ‘primitivising’ performance, to the notorious strangeness of the cult statue at Ephesus), Aphaia (and the various forms of female deity linking back to the mother goddess or mistress of the animals), Nemesis, Nike, Dione at Dodona, the Maenads, the Furies, the Sibyls, Electra, Hecuba, Clytemnestra, Circe, Persephone, Demeter, Helen, Andromache, Penelope, Cassandra, Medea, Antigone.

Honour to the culture, then – it may be a cruel conclusion – that gives a face and form to its misogyny. Because representing what it fears and abominates can be accompanied (not infallibly, but in the Greek case lavishly) by representations of what it can’t stop looking at, resenting and desiring. And, further, such a culture does not flinch from representations of misogyny itself – its horrors and absurdities, its pathos and automatism. Whether in the Greek case, or any other, this opened a space for actual day to day recognitions and negotiations around (against) the fictions Man and Woman, or even the beginnings of a way out of that instituted unreality, we shall presumably never know. But we inherit the representations. We can compare them with our own (sighing). We can make use of them. I think we should.

Return to Artemis in Piraeus. Focus on the larger bronze, especially its face, its ‘look’; but see it as part of the family of faces from Brauron and masks from Sparta; think of the Artemis as part of this culture’s great constellation of Furies and enchantresses and mistresses of the animal.

The Piraeus goddess is ‘serious’, I remember one of its discoverers writing. The word is a good one. Restraint seems to me the figure’s ruling emotion – restraint and responsiveness, restraint and some kind of compassion. Artemis, so the myths say, is a killer of men and beasts. She is jealous of her inviolate body. But her childlessness stands guard over the pains of childbirth. New life and death are intertwined. She is merciless and merciful – the legend does nothing to reconcile the two. They coexist, a mystery. I think the sculptor of the bronze was feeling for a way to show that mystery in a face – the face (the consciousness) holding more knowledge than it knows quite what to do with, stern, kind, discursive, abstracted, maybe ruthless (bow at the ready), maybe (this is a cult statue addressing its faithful) offering forgiveness or reassurance. Further, the face would surely not strike us as infused with such thought and feeling, however hard to translate, were it not part of a body – a pose, a fall of clothing, a balance of breast and implied abdomen, a careful but entirely confident reach into space – that speaks so astonishingly to thought and feeling in the body, done by the body as a whole. I would say that the Piraeus Artemis is the deepest reflection we have (with irony as part of the reflection) on the meaning, and limits, of the human stance as the Greeks envisaged it. Standing and understanding, with the enigma built into the latter word personified. Imagine the Piraeus figure, as some of her first viewers most likely would, as mistress of the animals, a dead deer or an exhausted lion dangling from each hand.

Relief of Actaeon and Artemis from Selinunte (c.470 BCE).

Imagine the figure in a gallery of gymnasts. Clothed to their nakedness, and unconcerned with bodily exertion; centre of gravity found and held; reach into space sufficient, almost expository; her body a column, fluted, segmented, immovable: with murder in reserve. Compare her to Artemis as she appears in the temple reliefs from Selinunte, carved around 470 BCE, looking on at the hounds as they tear Actaeon to pieces. The Piraeus sculptor, I feel, is reflecting on that older Artemis’ stance and expression.

Is the Met kouros indelibly, then – for all its composure – another Actaeon? Do we men and women not always look at his kind of manliness with an admiration subtended by pity and rage … by knowledge and foreknowledge of his death, by compassion for his vulnerability (his uprightness), and by a fear that has us always searching, consciously or unconsciously, for someone to blame: the Other who shot the arrow or loosed the dogs? Is the sphinx in the cabinet across the room in the Met the kouros’s necessary companion? The bird of prey … the chimera … the female whose riddle is better not solved?

Marble kouros side view.

Some of the time, I’ve been arguing, the Greeks would have answered ‘yes’ to the questions just put. But Artemis was a many-sided, mysterious god. She was the enemy of those she perceived as her enemy, and the protectress of those seeking her help. Actaeon, too, was a killer: those are his boar hounds turning against him. And the kouros in the Met was almost certainly a soldier: he has stepped out of his armour into his skin. The idea of masculinity, as this culture understood it, was built on these identities and behaviours; death in the front rank was beautiful, to be commemorated as such; but Greek art and literature from Homer onwards never stopped reflecting on the reality – the physical price – of glory. The Met kouros is mighty and vulnerable. Maybe this, most deeply, is what prolongs the nervous laughter in the gallery. The young man’s ‘equipment’ is fabulous. But something about the figure intimates that this is all it is – equipment, weaponry, the young man tied to it in death. And doesn’t the rest of the kouros’s body – its tentative stride, its balance and imbalance, its proportion and disproportion – call out for Artemis’ cruel steadying touch? Artemis Ortheia. Offering protection to youths as they prepare for manhood (meaning war) – but only if they put on the masks of old crones for an afternoon, caper absurdly, and submit to a lashing.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!