Balfour with Jewish settlers in 1925.

Fifteen years ago I was asked by a young Palestinian student at a meeting in Jenin whether, as a British subject, I felt responsible for the Balfour Declaration of 1917. Perhaps it was the translator who introduced the idea of personal responsibility, when the young woman who put the question meant historical. In any case, that’s how I remember hearing it and thinking that I was off the hook – no one in that room was alive in Balfour’s day or indeed in 1948. But young Palestinians have never forgotten the anger of earlier generations over the giveaway of lands they stood to govern after the Ottoman Empire crumbled. Arthur Balfour’s letter to Walter Rothschild affirming the British government’s support for ‘a national home for the Jewish people’ in Palestine was a milestone in the history of Israel’s creation, even if the idea dismayed a number of prominent British Jews at the time. Once it was enshrined in Article 4 of the League of Nations Mandate for Palestine, in 1922, it seemed a lot less tenuous than it had on paper. And it was possible by then to see it as one of several initiatives in support of a Jewish state. Five months before Balfour wrote to Lord Rothschild, the French diplomat Jules Cambon had approved ‘the Jewish colonisation of Palestine’ in a similar letter to Nahum Sokolow, Chaim Weizmann’s colleague and a member of the Zionist Executive. Sokolow had also secured the support of Benedict XV. Yet the Balfour Declaration is still seen by the British as a paramount contribution to the founding of a Jewish state, and Palestinians tend to agree.

During a debate in the House of Lords in 2017 about how best to commemorate the approaching centenary, there were moments of doubt. Lord Beith (Lib Dem) worried about the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, as did Baroness Hussein-Ece (Lib Dem); Lord Judd (Labour) wondered what had happened to the stipulation by Balfour that ‘nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine.’ By and large, though, the tone was robustly self-satisfied, with plaudits for Israel and Britain in equal measure. Lord Turnberg (Labour): ‘Israel owes an enormous debt to Britain … we should celebrate the fact that we in Britain provided the foundations of a democratic state in a part of the world where …’ etc. Baroness Deech (Cross-Bencher): ‘We celebrate the miraculous success of Israel; its world leadership in innovation; its thirteen Nobel Prize winners; its development of everything from the Intel processor to the five-minute cell phone charger, from radiation-free X-rays to desalination of sea water, from genetic counselling for the Bedouin to the epilator; its diversity and freedom of speech.’ Stuart Polak (Conservative) sought assurance that the Balfour centenary would be marked ‘with pride’ and took a moment to mention that his niece had ‘just named her new puppy after Balfour’. The main event of the centenary, it turned out, was a dinner for Netanyahu hosted by Theresa May. Banksy celebrated with an apology street party in occupied Bethlehem, where Elizabeth Regina, played by an actor, revealed a plaque cut into the Palestinian side of the separation wall with the words ‘Er … Sorry.’

Polak’s niece is not the first person to name an animal after Balfour. The Palestinian artist Ibrahim Ghannam was six at the time of the general strike in the Mandate in 1936. He was worried by Palestinian crowds taking to the streets and chanting ‘Down with Balfour.’ The real Balfour was dead by then but everybody, it seems, knew about the Declaration except Ibrahim. His brother had a pet monkey called Balfour: he went to the back yard and checked that it hadn’t escaped and caused a riot. When he told his story to Jonathan Dimbleby in the late 1970s, it must already have become a party piece. ‘From then on,’ he added, ‘I knew that the British weren’t our friends.’ Dimbleby’s The Palestinians, published in 1979, has been reissued with the original photos by Don McCullin and an annex of later ones by agency photographers as well as a new introduction. Dimbleby’s chapter on the ‘British responsibility’ for the Nakba is among the best in a book that should have dated but hasn’t. On the ground, the Palestinians’ asymmetrical fight for survival on a few scraps of land is no further along than it was when he wrote it. On the contrary.

The radical mood of the 1970s meant that Dimbleby and the Palestinians he spoke to were optimistic, even if memories of dispossession and doubts about the future shadowed their exchanges. (In the year his book appeared, Egypt and Israel concluded a peace with nothing tangible for Palestinians.) To read him nearly half a century later is to recognise that the many defeats the Palestinian population had already endured, along with those of their unreliable Arab friends in three humiliating regional wars, were preparations for worse to come, from the frenzied killing of Palestinian refugees in Sabra and Shatila by Lebanese Phalangist militias in 1982 under Israeli supervision, through the flash sale of Palestinian gains after the first intifada with the Oslo Accords in 1993 and 1995, and on, after the Hamas attack in 2023, to the annihilationist war in Gaza and a rise in settler crimes on the West Bank. The future of the Palestinians, like the future of their tormentors, looks bleaker now than it did when the book was published.

There are several British players in his chapter on events during the Mandate. Some had misgivings about their roles as colonial masters. Alec Kirkbride, district commissioner for Galilee, recalled having to attend the hanging of three young Palestinians in Acre during the Arab uprising and being overwhelmed by ‘the feeling that I was doing something shameful’. It’s a very British framing of the troubled conscience, like Orwell’s in ‘A Hanging’, published in 1931, five years before the revolt in Palestine began. In 1936 Hugh Foot, assistant district commissioner for Samaria, signed a three-month detention order for Akram Zuaiter, a young nationalist in Nablus whose father had held provincial office under Ottoman rule. Three months in a camp, with a reliable release date, looks trifling by comparison with the horrors unfolding in Israeli jails and military bunkers, but at the time of the uprising, Foot felt he was crossing a line. He went on as Britain’s permanent representative at the UN to sponsor Resolution 242, in 1967, which called on neighbouring states to concede Israel’s right to ‘live in peace within secure and recognised boundaries’ and on Israel to withdraw from the territories it had taken in the Six-Day War. Foot wrote a conciliatory letter to Zuaiter and a poem in which he imagines the two of them in Nablus ‘acknowledging as just and true/the principles of two-four-two’. But for a range of reasons, including the fact that the Palestinians were stateless and the UN failed to recognise them as a people with national rights, the resolution was reviled by the PLO until 1988, when Arafat made his Palestinian Declaration of Independence in Algiers.

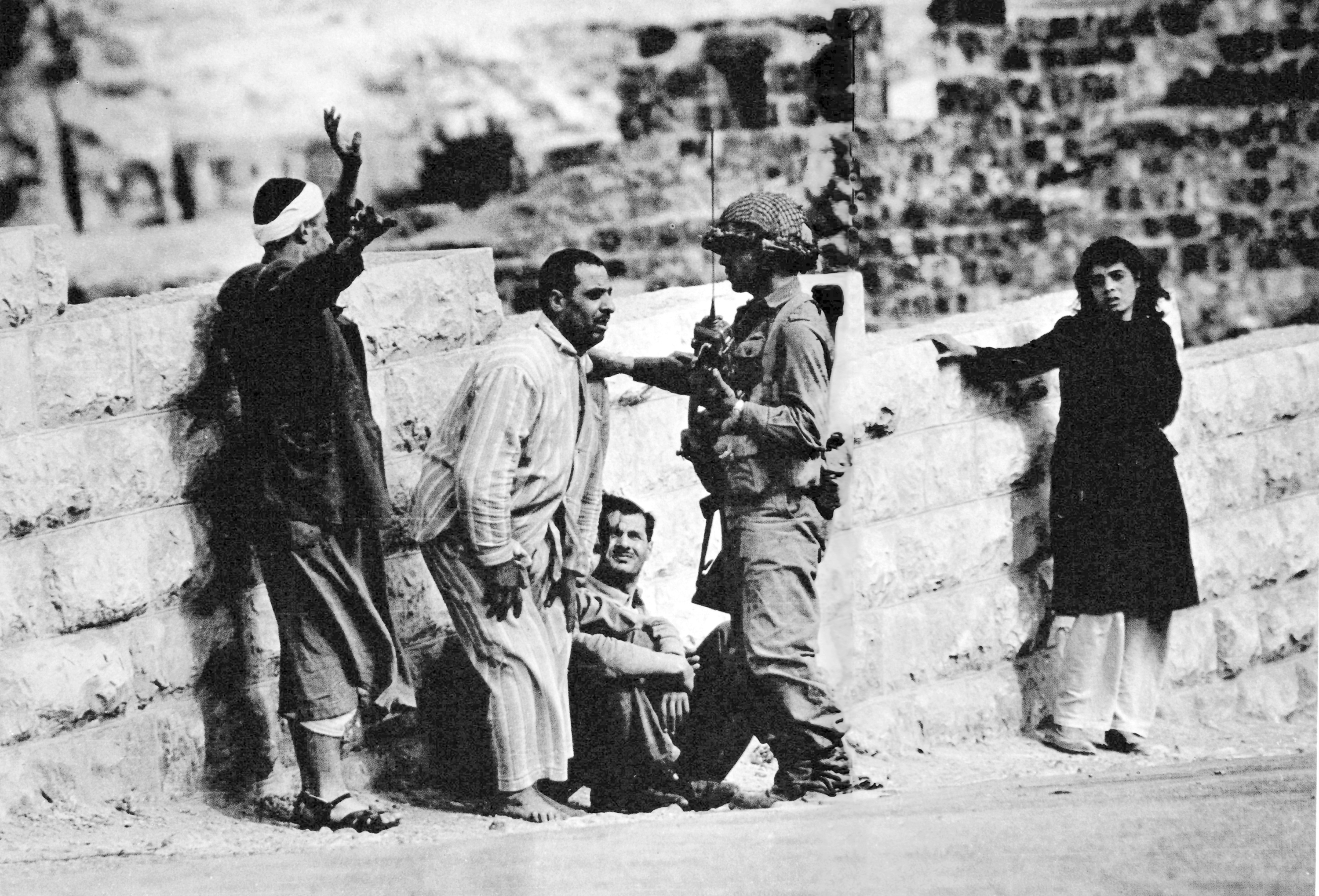

Occupied East Jerusalem in 1967, photographed by Don McCullin.

Expressions of colonial regret like Foot’s give only a modest glimpse of how much there was to atone for. Dimbleby cites the standard figures for the pacification of the Arab revolt – more than a hundred hangings and a thousand Palestinians dead in its first year (a total that would rise to five thousand by the time it was over in 1939). Older Palestinians he speaks to recall the cruelty and chaos: collective punishment, food confiscation, quarantining of villages, beatings and mass detention – all routine measures for European colonial administrations at the time and earlier. As the story moves into the 1960s and 1970s and Dimbleby’s interlocutors get younger, McCullin takes his cameras into Palestinian guerrilla training camps, where young men being put through their paces seem to emulate the charismatic violence of the Zionist paramilitaries who expelled their grandparents in 1948. In both cases the gun was a remedy for humiliation – the shame of the Holocaust on the one hand, the shame of eviction and expropriation on the other. But as a military force the fedayeen were outgunned and outmanoeuvred by their allies and so-called friends, and above all by Israel.

The Palestinians is a montage of interviews and encounters structured by long passages about the historical context. It was meant to clear up the mystery of Palestinian identity for a British audience. Plane hijackings and assassinations by various factions of the PLO had drawn the world’s attention to the Palestinian cause and produced a handful of emerging celebrities, most obviously Leila Khaled, the star of two high-profile hijackings a few years before the murders at the Munich Olympics in 1972. Dimbleby wanted to hear from less conspicuous Palestinians, and they didn’t need much persuading. McCullin’s eye opened up a view of Palestinians that was rich and complex: fighters of course, but equally medics, people in business, landless farmers, refugees fleeing their assailants in Lebanon or mourning their dead; also wealthy members of the nationalist bourgeoisie in exile, driven from their homes in Haifa and Jaffa in 1948. The Palestinians became real, accessible people whose stories, across class tensions and political differences, were compelling, like those of the East Timorese, the Sahrawis in former Spanish Sahara, the majority populations of Rhodesia, South Africa and Namibia, at a time when colonialism seemed to be heaving its last, reluctant sigh. Edward Said and the photographer Jean Mohr published After the Last Sky, a more intimate look at Palestinian lives under pressure, with rich passages of memoir by Said, in 1986, on the eve of the first intifada.

Dimbleby was generous to the PLO. Maybe he looked well on their armed struggle because he thought it would favour the Palestinian case in the event of a negotiated settlement. If so, time has proved him wrong, along with the many people he interviewed. Years after his book appeared, the Palestinian leadership gambled on civil rights, international law and non-violent co-existence as a balkanised state alongside Israel. This did not pay off either. Yet Israel’s longstanding ‘Palestinian problem’ hasn’t gone away. The government’s approach to this large difficulty – two million hostile subjects in Gaza, roughly the same number of ambivalent or angry Palestinian citizens of Israel and another three million stateless persons on the West Bank trying to defend their land – is sophisticated and multifaceted, both outward and inward-facing, ruthless and unpredictable. Most recently, through an obscure travel agency, it packed off a charter flight of 153 Gazans who could afford a seat to Johannesburg, apparently without official clearance from South Africa – a grudge destination for Israel ever since the South Africans brought a case at the International Court of Justice alleging genocide in Gaza. Tinkering at the edges of ethnic cleansing in this way seems odd for a government that set out with a measure of success to exterminate the brutes in Gaza in response to the killing spree by Hamas that externalised 75 years of misery and threw it back in Israel’s face. But it’s not as footling as it looks. Before long we’ll be hearing from Israel’s hasbara spokespeople about the hypocrisy of a country that alleges a Palestinian genocide but makes a fuss about taking in Palestinian refugees. It’s an ingenious way of trolling South Africa and funnelling Palestinians out of their devastated territories. The ethnic cleansing of Palestinians is a long haul for Israel, and every little helps.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!