When Samuel Pepys , wifeless and childless, died in 1703, the pride of his life – three thousand books, lavishly gilded and bound in brown leather – passed to Magdalene College, Cambridge, where he had once been a student. The college had scarcely any record of him apart from a reprimand for ‘having been scandalously overseen in drink’, but that no longer mattered. The bequest included medieval manuscripts, important naval documents, an early copy of Isaac Newton’s Principia and Francis Drake’s personal almanac. Nearly everything in the Bibliotheca Pepysiana – as Pepys insisted it forever be called – was tantalisingly rare and had become even rarer after the Great Fire devastated London booksellers. Magdalene was in no position to refuse (its own books were covered in mould), and didn’t object to any of Pepys’s conditions; if it had, the collection would have gone to Trinity College. The rules were ironclad: the Bibliotheca Pepysiana was to be housed in a ‘fair roome’, with no volume ever to be struck from the collection and ‘no other books mixed therein’; no book was to go outside except to the master’s lodge, and then no more than ten at a time. To keep Magdalene honest, Trinity was requested to inspect the library annually, and to be ready to pounce.

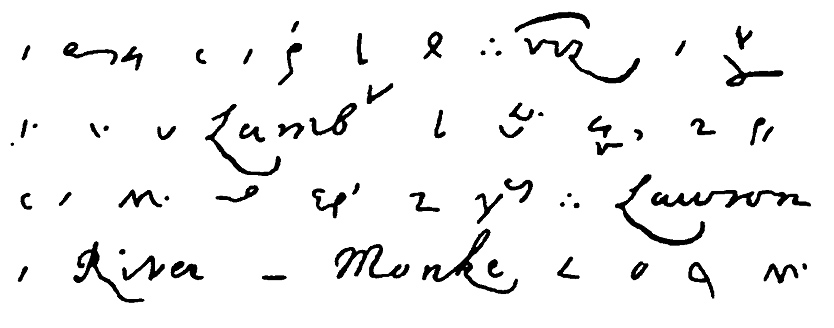

A hundred years went by. The Bibliotheca Pepysiana (still at Magdalene) became known chiefly for its trove of 17th-century ballads, which supplied Bishop Percy with material for his Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. Pepys himself was remembered, if at all, as a naval administrator who’d had a compulsion for buying up printed paper. The library’s catalogue – it wasn’t a secret – listed six volumes of his diaries, but no one read them. The sentences looked like this:

In 1818, a different diary was published: Memoirs Illustrative of the Life and Writings of John Evelyn, trumpeted as an eyewitness account of life at the court of Charles II. It was often less than thrilling – ‘21 June, 1653. My Lady Gerrard, and one Esquire Knight, a very rich gentleman, living in Northamptonshire, visited me’; ‘23 June, 1653. Mr Lombart, a famous graver, came to see my collections’ – but was a commercial success nevertheless and reissued throughout the 19th century. In The Common Reader, Virginia Woolf confessed to disappointment: Evelyn was a ‘gentleman of the highest culture and intelligence’, but a diary ought to reveal ‘the secrets’ of the ‘heart’ and he’d written nothing that couldn’t have ‘been read aloud in the evening with a calm conscience to his children’. Still, if you wanted a personal chronicle of the plague (‘The pestilence now fresh increasing in our parish, I forbore going to church’) or the fire (‘the whole city in dreadful flames near the waterside’), what else was there? At last, Magdalene stirred. Kate Loveman’s new book traces the way Evelyn’s triumph prompted the master, George Neville, to consider whether he ought to do something about the 17th-century diary in his collection. He lent the first volume to an uncle, who passed it to another uncle, who advised Neville to find ‘some man for whom the lucre of gain will sacrifice a few months to the labour of making a complete transcript’. He also warned his nephew not to tell anyone that he’d taken Pepys’s diary to Buckinghamshire, or they could lose the whole shebang.

In Samuel Pepys: The Unequalled Self (2002), Claire Tomalin calls what followed a ‘tragi-comedy’. Her account, which has become the standard narrative of the diary’s transcription, has Neville hiring an impecunious undergraduate, John Smith, to produce a readable version of Pepys’s diary – 1.25 million words, longer than Shakespeare’s complete works – for £200. What Neville’s uncle imagined would take a few months dragged on for three years, with Smith claiming that he often laboured ‘for twelve and fourteen hours a day’ to break Pepys’s code: an alphabet of symbols (a was ^, b a vertical stroke), but with some letters sharing signs, and vowels indicated either by their own marks or by the position of the next consonant, with special squiggles for common letter pairs and some whole words. Smith grandly styled himself Pepys’s ‘decipherer’, apparently unaware that Pepys had written the diary in Tachygraphy (‘swift writing’), a shorthand system that had once been popular with students and sermon note-takers, and was later used by Thomas Jefferson. Pepys had included a tachygraphy manual in the Bibliotheca Pepysiana, and Tomalin concludes that poor Smith ‘carried out the entire task without knowing that the key to the shorthand was in the library’. Loveman’s careful analysis of the transcripts suggests that this is almost certainly tosh: Smith made use of the manual from the start, but kept it quiet, probably to finagle a bit more money. He was twenty years old and already supporting a wife and child. For most of the 19th century, Smith would be the only one to read what Pepys actually wrote, and generations of readers had little choice but to assume his transcription was accurate.

When the diary begins, on 1 January 1660, Pepys is 26 years old, a part-time clerk at the Exchequer, living in Westminster. He affirms that he’s in good health, ‘esteemed rich, but indeed very poor’, and uncertain whether he’ll be able to keep his job if the Commonwealth collapses and Charles Stuart returns from The Hague. The first entry charts his wife’s menstrual cycle: ‘after the absence of her terms for seven weeks’ he had ‘hopes of her being with child, but on the last day of the year she hath them again’. He never explains why he begins keeping a diary – only why, nine years later, he stops (poor eyesight). Evelyn would continually revise entries long after he’d written them, but Pepys doesn’t edit his sentences for posterity. He knows that what he’s setting down isn’t fit for his household or ‘all the world to know’. But the early entries are misleadingly innocuous. He writes about what he’s wearing (‘my suit with great skirts’) and that he’s just heard a ‘very good sermon’ on the circumcision of Christ. He writes that he ‘stayed at home all the afternoon, looking over my accounts’ while his wife – never named, only ever ‘my wife’ – ‘dressed the remains of a turkey, and in the doing of it she burned her hand’. When he goes with her to his father’s house, ‘in came Mrs The. Turner and Madam Morris’ – c’est tout. Evelyn would have placed them in the world: ‘the estimable Mrs Theophilia Turner and the discreet Madam Morris, my father’s worthy friends’. But Pepys doesn’t see the need, not if he’s only writing for himself.

Pepys had risen – inasmuch as he had – through the Cromwellian bureaucracy. If a new regime cleaned house, he didn’t have much to fall back on. There were no Pepyses in The History of the Worthies of England (he read it all the way through, hoping against hope). His father was a tailor. His mother had been a laundry maid before her marriage. There were ten other children – Samuel was the fifth, and would be the oldest to survive into adulthood. But although his father could only write a little, and his mother not at all, he was able to attend a grammar school and then St Paul’s, reputed to be the most Puritan of all the London schools. When he was fifteen, he was in the crowd for the execution of Charles I – he very much approved. During the Restoration, seeing old school friends would make him uneasy, in case they ‘remembered the words that I said the day the King was beheaded’. Scholarships took him to Cambridge, where he might have been expected to prepare for the law or the church, but he doesn’t seem to have pursued any particular career. Illness may have checked his ambition: bladder stones left him in a ‘condition of constant and dangerous and most painfull sickness’. Later he would recall that not a single moment of his youth had been without pain. Yet when the diary begins, he’s exultant. The ‘great stone has finally been cut out – an operation so brutal and perilous that no one who wasn’t in absolute agony would have consented to it. Afterwards he kept the stone, nearly the size of a tennis ball, in a case and marked its removal each year with a feast. He felt, at last, that his life was worth recording.

In February 1660, Pepys noted that the government was so unpopular that ‘boys do now cry “Kiss my Parliament” instead of “Kiss my arse.”’ A few weeks later, ‘everybody now drinks the King’s health without any fear, whereas before it was very private that a man dare do it.’ He had one great familial connection: a distant cousin, Edward Montagu, had risen through the ranks of the Parliamentary army and then become joint general at sea. After Cromwell’s death, Montagu switched sides, and – though Pepys didn’t know it – opened a secret line to the royal court in exile. Pepys would later lament ‘how little merit doth prevail in the world, but only favour – and that for myself, chance without merit brought me in.’ On 6 March, Montagu asked whether Pepys ‘could without too much inconvenience go to sea as his Secretary’: he was bound for Holland to convey Charles Stuart back to England. Pepys was apprehensive – he wrote his will and wondered if he ‘should scarce ever see my mother again’ – but curiosity prevailed. He’s ‘with child to see any strange thing’. He also senses that, if the Restoration is unstoppable, this service may be the making of him. Although he can’t pay the rent on ‘my poor little house’ without going into debt, he can see the future: himself a great man, his wife no longer obliged to keep household accounts ‘even to a bunch of carrot’. But ambition makes him anxious. He prays to God to ‘keep me from being proud or too much lifted up hereby’, a flash of the moral double-entry bookkeeping that will come to define the diary. By the end of May, he’s on the Dutch coast, kissing all the royal hands.

The king is ‘quite contrary’ to Pepys’s expectations – he’s ‘sober’, yet also ‘active and stirring’, undeniably dashing, seemingly the embodiment of royalist propaganda. Pepys is entirely taken in, ‘ready to weep’ as Charles recounts his escape after the Battle of Worcester: ‘travelling four days and three nights on foot, every step up to the knees in dirt’, wearing poor shoes that ‘made him sore all over his feet’, recognised incognito by an innkeeper who ‘kneeled down and kissed his hand privately, saying that he would not ask him who he was, but bid God bless him whither that he was going’. Just when the diary seems to have devolved into gooey reverence – as if Pepys has started writing for a wide Cavalier audience – he snaps back to record his ‘strange dream of bepissing myself, which I really did; and having kicked the clothes off, I got cold and found myself all muck-wet in the morning and had a great deal of pain in making water, which made me very melancholy.’

Montagu had promised Pepys that they would ‘rise together’ – and so they did. Even before Charles II was crowned at Westminster, Pepys was made ‘clerk of the acts’ to the Navy Board and deputy at the Privy Seal. In one stroke, he had become one of the most powerful men in the civil administration of the navy, overseeing shipbuilding, maintenance, stores and provisions. The appointments came with a house by Tower Hill, and paid well, but Pepys quickly worked out that it wasn’t the ‘salary of any place that did make a man rich, but the opportunities of getting money while he is in the place’. Loveman shows how the diary became Pepys’s secret ledger, the place for him to record bribes (‘considerations’) and the elaborate justifications he might one day need to defend them. After a Captain Grove, whom Pepys helped secure a desirable posting, handed him a letter, he writes: ‘I discerned money to be in it and took it’ – a gold piece and £4 in silver. But no less important to Pepys was the performance of his own honesty: ‘I did not open it till I came home to my office; and there I broke it open, not looking into it till all the money was out, that I might say I saw no money in the paper if ever I should be Questioned about it.’ It was hardly a brilliant defence, and it’s just as well he never had to test it.

Pepys was a meticulous – some might say compulsive – record-keeper, and his talent for storing and retrieving vast amounts of information would be useful to him throughout his career. Loveman argues that the diary became his ‘catch-all’ for anything he couldn’t safely or conveniently note in his official or household accounts. Into its pages went social debts (who had given him dinner, who still owed him one), gossip, the music he heard and the plays he saw, and the most intimate aspects of his life, from bodily functions (including what has been called ‘one of the best documented attacks of flatulence in history’) to sex.

He had married Elizabeth de St Michel when he was 22 years old; she was 14, young even by the standard of the time. We don’t know how they met. Her father was French, and she had grown up in Paris and Devon. She was a Protestant, though when she was angry at her husband she would sometimes threaten to convert to Catholicism. He thought that he was in love with her, at least at the beginning of their marriage. When he hears an especially stirring piece of music, he writes that it did ‘wrap up my soul so that it made me really sick, just as I have formerly been when in love with my wife’. By the time the diary begins, Pepys records frequent arguments – sometimes over Elizabeth’s dog (‘my wife and I had some high words upon my telling her that I would fling the dog which her brother gave her out at the window if he pissed the house any more’), sometimes because she’s lonely or jealous, and doesn’t want Samuel to leave the house without her. He’s proud that she’s ‘much handsomer’ than the women in the royal family, and resentful that she brought no money to the marriage, ‘nothing almost (besides a comely person)’. He enjoys teaching her music and arithmetic, and misses her when he’s in Holland. He also gives her a black eye ‘for not commanding her servants as she ought’, and turns peevish and cruel when she’s in too much pain (possibly from endometriosis) to sleep with him. When she realises that he’s been unfaithful, ‘my poor wife’ flew into a ‘horrible rage’. For several weeks she refused to wash herself, and ‘could not refrain to strike me and pull my hair, which I resolved to bear with, and had good reason to bear it’. She died of what was probably typhoid fever when she was 29, just a few months after Pepys stopped keeping a diary.

When the undergraduate John Smith prepared the first transcription, plenty of sentences were left out. He was probably exercising discretion – he often indicated an omission by writing ‘obj’ for ‘objectionable’ – but he may also have been registering defeat: Pepys’s shorthand becomes enormously tricky to decipher whenever he writes about sex. English words are distorted with extra consonants (‘dummy letters’), and he often slips – sometimes only for a word or two – into Greek, Latin, French, Italian, Spanish and what might be Portuguese. When he lifts a servant girl onto his lap, it’s ‘con my hand sub su coats; and endeed, I was with my main in her cunny’. Or when he masturbates in church, thinking of a friend’s daughter: ‘(God forgive me), my mind did courir upon Betty Mitchell so that I doth hazer con mi cosa in la eglise.’ Loveman suggests that the difficulty of deciphering these passages can’t be overstated; generations of transcribers have struggled with them, prudish or not. They appear only sparingly at first, then take over. By the end of the diary, Tomalin describes Pepys going ‘out on his rounds like an animal’ – prowling Westminster and beyond for a woman or girl who would ‘tocar’ his penis or let him kiss her ‘mamelles’, or in his favourite phrase, ‘do what I would with her’. Sometimes the teenage girls he pursued worked in his household (their number grew as he went up in the world) and in the houses of his friends, or he met them while shopping in Westminster Hall and the Royal Exchange, and at street markets. But for penetrative sex he seems to have preferred married women whose husbands worked for the navy, whose interests he could advance in return. Pepys worried about pregnancy, and marriage offered a cover, though his biographers usually assume he was sterile, possibly as a consequence of the bladder stone surgery.

Loveman argues that modern discussions of Pepys usually recognise that he exploited women, but sidestep the possibility of rape. She highlights an entry from 1664, in which Pepys meets with Bagwell, a ship’s carpenter, who brings him to his house. ‘After dinner I found occasion of sending him abroad,’ he writes, and then being ‘alone’ with Bagwell’s wife, ‘je tentoy à faire ce que je voudrais, et contre sa force je le faisoy, bien que pas à mon contentment’ (‘I tried to do what I would, and against her will I did it, though not to my satisfaction’). A few months later, he writes: ‘I had sa compagnie, though with a great deal of difficulty; néanmoins, enfin je avais ma volonté d’elle’ (‘I had her company, though with a great deal of difficulty; nevertheless, finally I had my will of her’). The next day he notes a ‘mighty pain’ in the forefinger on his left hand from a ‘strain that it received last night in struggling avec la femme que je mentioned yesterday’. Loveman acknowledges that ‘I had my will of her’ could denote seduction as well as coercion: the phrase is used both ways in other contexts. There’s room for reasonable doubt, she concludes – but only just.

The first official editor of Pepys’s diary was the master of Magdalene’s brother, Richard Neville, then on the verge of inheriting a peerage. He later claimed that he would have preferred to devote himself to the management of his estate – Audley End in Essex, often seen in TV dramas pretending to be Windsor or Balmoral – but he prepared Smith’s manuscript for publication out of a sense of family duty. Neville said he intended to preserve only what he considered to be in the ‘public interest’, with anecdotes that served to ‘illustrate the manners and habits of the age’ and an emphasis on the diary’s great set pieces: the coronation of Charles II (which Pepys partly missed because it was difficult to find a place near the abbey to piss) and the Great Fire, when Pepys frantically dug a pit to protect his wine and Parmesan, yet still paused to record how ‘the poor pigeons … were loth to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconys till they were, some of them burned, their wings, and fell down.’ Pepys’s personal life was largely excised, which doesn’t mean that the first edition of the diary was sexless: Neville decided that Charles II’s affairs fell under ‘public interest’, though ‘whores’ were silently upgraded to ‘mistresses’. By the time the diary first went on sale in 1825, Neville had become Lord Braybrooke, lending the whole enterprise an aristocratic sheen, and reviewers would deferentially refer to Pepys’s ‘noble editor’. The edition itself was a luxury item: six guineas for two large volumes (only about a quarter of the original diary), complete with engravings. Some reviewers wondered if it had been designed to ‘warn away the commonality of readers’; in any case that was the effect.

Braybrooke was eager to present Pepys as morally serious, even grave, and in this he almost succeeded: Walter Scott, reviewing the first edition in 1826, declared that Pepys had ‘no crimes to conceal, and no very important vices to apologise for’. He praised Pepys for remaining at his post during the plague (a period Pepys found unexpectedly enjoyable, especially after his wife decamped to the countryside), and lauded his role in reforming the Restoration navy. Scott wasn’t wrong: Pepys did help professionalise the service, not least by instituting competency exams for officers, even as he continued to pocket the considerations that came with the old system. A few months after Scott finished reading the diary, he started keeping his own, and would sometimes imitate Pepys’s style: ‘J. Ballantyne and R. Cadell dined with me, and as Pepys would say, all was very handsome.’

Loveman traces the way Braybrooke’s edition first informed, then gradually commandeered, English histories of the 17th century. For Scott, as for others, Pepys’s diary seemed ‘so rich … in every species of information concerning the author’s century’ that no other source could rival it. For Thomas Babington Macaulay, in the midst of preparing The History of England, the diary ‘formed almost inexhaustible food for my fancy’. He was particularly struck by Pepys’s report of a woman miscarrying a baby while dancing at a court ball, ‘but nobody knew who, it being taken up by somebody in their handkercher’. According to the story – which Pepys learned third-hand at best – Charles II supposedly kept the foetus and ‘had it in his closett a week after, and did dissect it; and making great sport of it, said that in his opinion it must have been a month and three hours old’. Macaulay used the episode to denounce the ‘crimes and follies’ of the dissolute Caroleans. Yet his growing reliance on the diary made him uneasy; he later recalled that he once dreamed that his young niece

came to me with a penitential face, and told me that she had a great sin to confess; that ‘Pepys’s Diary’ was all a forgery, and that she had forged it. I was in the greatest dismay. ‘What! I have been quoting in reviews, and in my History, a forgery of yours as a book of the highest authority. How shall I ever hold my head up again?’ I awoke with the fright, poor Alice’s supplicating voice still in my ears.

More – and more complete – versions of Pepys’s diary proliferated in the 19th century, and errors were rampant. Editors silently rewrote passages that seemed tawdry, or just left them out; it was routine to excise Pepys’s sexual escapades while preserving his wife’s rages, which just made her seem unhinged. Pepys was finally permitted his first extramarital ‘embrace’ in 1877 after Mynors Bright, a retired president of Magdalene, issued a six-volume edition of the diary. Robert Louis Stevenson, reviewing it in the Cornhill Magazine, could tell that much was still missing – stories often didn’t cohere – and complained that ‘when we purchase six huge and distressingly expensive volumes, we are entitled to be treated rather more like scholars and rather less like children.’ In 1933, plans to publish the diary in its entirety were announced in the Times Literary Supplement, but the project collapsed when the editor, Francis Turner, Great War flying ace and the Bibliotheca Pepysiana librarian, re-enlisted at the outbreak of the Second World War. It might have been doomed anyway: publishers were wary of violating the Obscene Publications Act and the Hicklin test. If even anatomical textbooks were being suppressed, what hope was there for honest Pepys?

In 1960, while Penguin was being prosecuted for the publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Magdalene sought the advice of its fellows on whether to proceed with a complete edition. C.S. Lewis argued that it would be ‘pusillanimous and unscholarly’ to hold back. Society, he wrote, was already so corrupted that the supposed further harm of ‘printing a few, obscure and widely separated passages in a very long and expensive book, seems to me unrealistic or even hypocritical’. Two days before Penguin was acquitted, the Magdalene bursar signalled that a complete edition would be allowed to go ahead. Robert Latham, a Magdalene fellow, undertook the work with William Matthews, an English professor at UCLA. Their transcription was astonishingly accurate, especially given that much of it had to be done overseas from poor-quality photocopies. But the two men eventually fell out, and Matthews threatened to go to the press with evidence that the diary had routinely left college grounds – for instance, when it had been taken to the Cambridge University Library for photocopying. A ‘peace was brokered’, Loveman reports, and their edition came out in nine volumes, between 1971 and 1983, with extensive footnotes, a thorough index and a companion volume of background information. The Times called it ‘one of the glories of contemporary English publishing’, while the Observer described it as ‘one of the finest feats in all the long history of scholarship’ and quoted Horace: ‘Exegi monumentum aere perennius.’ Loveman’s research shows what it took to bring a complete edition of Pepys to market. Her book is scrupulous and exciting, and should almost certainly be read by someone at Trinity College.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!