In 1676, during the period of colonial conflict known as King Philip’s War, Reverend Hope Atherton was the chaplain accompanying Captain William Turner’s militia on their march to an Algonquian encampment near Deerfield, Massachusetts in the Connecticut River Valley. There they ambushed the sleeping tribe, slaughtered some of them and drove others into the river, which swept them over the waterfall – now known as Turners Falls – to their deaths. As the army retreated, they came under a counter-attack that killed many, including Turner. A few scattered survivors got lost in the woods, some wandering for days before stumbling back to their settlements. Atherton was among them.

Susan Howe took Atherton’s ordeal after the ‘Falls Fight’ as the focal point for her poem sequence ‘Articulation of Sound Forms in Time’, which was published as a chapbook in 1987 and later collected in Singularities (1990). It was his name that first caught her attention; in the prose exposition that begins the poem, she wrote: ‘Hope’s epicene name draws its predetermined poem in.’ But it’s in the conjunction of that name with the bewilderment in the forest, and the consequences of wandering, that the poem is ‘predetermined’. Howe includes an excerpt from a clergyman’s letter, dated a century later, detailing his discovery of Atherton’s sermon about his experience:

Mr Atherton gave an account that he had offered to surrender himself to the enemy, but they would not receive him. Many people were not willing to give credit to this account, suggesting he was beside himself. This occasioned him to publish to his congregation and leave in writing the account I enclose to you.

This, a reimagining of his sermon, is where ‘Hope Atherton’s Wanderings’ begins:

Prest try to set after grandmother

revived by and laid down left ly

little distant each other and fro

Saw digression hobbling driftwood

forage two rotted beans & etc.

Redy to faint slaughter story so

Gone and signal through deep water

Mr Atherton’s story Hope Atherton

‘Gone and signal through deep water’ alludes to Atherton’s actual sermon:

Two things I must not pass over that are matters of thanksgiving unto God; the first is that when my strength was far spent, I passed through deep waters and they overflowed me not according to those gracious words of Isaiah 43:2; the second is, that I subsisted the space of three days & part of a fourth without ordinary food.

But what is the provenance of the rest of Howe’s hallucinatory lines? The reader staggers through them as if through an oneiric forest of phrases. As you proceed through the 35-page sequence of rhythmic, gnomic lyrics, you surrender the need for sense and syntax as Atherton surrendered the need for food:

I thought upon those words ‘Man liveth not by bread alone but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of the Lord.’ I think not too much to say that should you & I be silent & not set forth the praises of God through Jesus Christ that the stones and beams of our houses would sing hallelujah.

The expressive power of the sequence derives not just from lyricism but from the anguish of what is withheld.

‘Articulation of Sound Forms in Time’ is bundled together with two other sequences, ‘Thorow’ and ‘Scattering as Behaviour towards Risk’, establishing Singularities as an early example of the form that characterises Howe’s later books: three or four lyric sequences of varying length centred on historical figures or events, each beginning with a prose exposition in her sibylline style, moving into increasingly fragmentary lyrics and culminating in concrete poems – sometimes unreadable or unsayable – assembled through cut-and-paste and xerox collage. ‘Scattering as Behaviour towards Risk’ ends:

Collage is used at every scale: a book is a collage of sequences; each sequence is a collage of epigraphs, lyrics and quotations. The quotations come from literature, letters, diaries, from facsimile editions and concordances. Archival research is part of the fabric of the work, and paeans to library architecture and stacks appear within the poems. Howe quotes Wallace Stevens’s ‘poetry is a scholar’s art’ while speaking of Emily Dickinson, but also (of course) herself. The library is her forest, and Howe is – with just one letter swapped – Hope.

Recent textual scholarship focusing on Dickinson’s ‘envelope poems’ owes much to Howe’s writings on the visual interest of the holographs. Her book My Emily Dickinson (1985) is a thrilling work of criticism – an indisputable cult classic – written outside contemporary academic protocols, a throwback to something like John Livingston Lowes’s The Road to Xanadu or Charles Olson’s Call Me Ishmael (an influence Howe acknowledges). It’s an unorthodox close reading of ‘My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun’, which encompasses, among other things, the American Civil War, Wuthering Heights, Richard III and Robert Browning’s ‘Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came’.

Singularities was written on the heels of My Emily Dickinson. I picked it up soon after it was published, accustomed by then to what was broadly, and belligerently, in the air at the time: theory, postmodernism, Language poetry. ‘Indeterminacy’ was the new ambition, pursuant to a ‘surrogate social struggle’, according to Ron Silliman’s introduction to the Language poetry anthology In the American Tree (1986). But Howe stood apart, and time has vindicated the sense that she is more the child of New England Transcendentalists than of the international Marxist-materialists bandied about in those days. Her geographic span covers southern New England, her father’s domain, and Ireland, where her mother was born. Her temporal range extends from the Reformation to the present, barely granting a distinction between then and now. She went to art school, not university, so the visual arts have exerted a lasting influence on her, not least in the way each book, each series, revolves around a concept. Some of her titles sound like multimedia installations and her concrete poem-collages are as much artworks as texts (her mentors included Ian Hamilton Finlay, with whom she had an early correspondence).

Decades later, Singularities still looks like a breakthrough. It teems with associations and it’s possible to feel, two-thirds of the way through, that one has completely lost the thread. A concatenation of forces topples over into chaos (then, eventually, rights itself). This is no accident. The ‘singularity’, as Howe put it in an interview, ‘is the point where there is a sudden change to something completely else. It’s a chaotic point. It’s the point chaos enters cosmos, the instant articulation.’ She uses it as a metaphor for Europeans coming to America. She enacts it in her book-length journeys from serene prose to violent fractured collages.

Revisiting Atherton in Souls of the Labadie Tract (2007), Howe writes: ‘I vividly remember the sense of energy and change that came over me one midwinter morning when, as the book lay open in sunshine on my work table, I discovered in Hope Atherton’s wandering story the authority of a prior life for my own writing voice.’ She goes on to say that her move from Manhattan back to New England in 1972 – she was born in Boston – revived in her an atavistic ardour: ‘This particular landscape, with its granite outcroppings, abandoned quarries, marshes, salt hay meadows and paths through woods to the centre of town, put me in touch with my agrarian ancestors.’

She walked where her ancestors had walked: this is why Atherton’s journey on foot struck an imaginative nerve, and why she connects it to Thoreau’s essay ‘Walking’ (1862). In Souls of the Labadie Tract, her meditation on Stevens begins by citing the fact that he walked to work and back every day for 22 years. On these walks, she reminds us, he composed his poems:

Stevens … observed, meditated, conceived and jotted down ideas and singular perceptions, often on the backs of envelopes and old laundry bills cut into two-by-four inch scraps he carried in his pocket. At the office, his stenographers, Mrs Hester Baldwin and Marguerite Flynn, made transcripts. During night hours and on weekends, he transformed the confusion of these typed up ‘miscellanies’ into poems.

This prose section is followed by a poem sequence, ‘118 Westerly Terrace’ (Stevens’s home address in Hartford), which takes its epigraph from Henry James (‘His alter ego “walked”–’) and begins:

In the house the house is all

house and each of its authors

passing from room to roomShort eclogues as one might

say on tiptoe do not infringe

Howe is reworking Stevens’s ‘The House Was Quiet and the World Was Calm’, a poem of repetitions that become recursions as ‘the reader became the book,’ and the summer night ‘itself/Is the reader leaning late and reading there’. In Howe’s poem the repetitions similarly suggest yearning for a commingling:

Face to the window I had

to know what ought to be

accomplished by predecessors

in the same field of labour

because beauty is what is

What is said and what this

it – it in itself insistent is

Poets aren’t the only presiding influences on Howe’s work. Alongside Atherton, other figures from Puritan New England loom large: Increase Mather (born in Boston in 1639, the sixth president of Harvard College) and his son Cotton Mather (who defended the Salem witch trials); Jonathan Edwards (1703-58), whom Howe calls ‘the most astute and original American philosopher to write before the age of James, Peirce and Santayana’. She is interested in heretics, scapegoats and controversialists: Anne Hutchinson (1591-1643), ‘excommunicated and banished by an affiliation of ministers and magistrates for the crime of religious enthusiasm’; Margaret Fuller (born in Cambridge in 1810), Transcendentalist, women’s rights advocate, journalist and the first editor of Emerson’s magazine, the Dial. (Fuller drowned on a return voyage from Italy when her ship foundered on a sandbar off the coast of Fire Island. Emerson sent Thoreau to scour the shore for signs of her or her manuscripts.) Mary Rowlandson (1637-1711) is another touchstone. Like Atherton, she endured a period of errancy in the New England wilderness. Captured with her children by the Narragansetts, she later recounted her survival and escape in A Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs Mary Rowlandson, a work that, according to Howe, gave rise to ‘the only literary-mythological form indigenous to North America … a microcosm of colonial imperialist history and a prophecy of our contemporary repudiation of alterity, anonymity, darkness’.

And yet one wouldn’t say that Howe programmatically divides the colonists into the powerful and the marginalised. New England was the margin for these farmers, builders and theologians trying ‘to impose order on a real wilderness where winters were harsh, where wolves howled around the outskirts of each settlement, and a successful harvest often meant life or death to the community’. She goes on:

The idea that our visible world is a whim and might be dissolved at any time hung on tenaciously. It was this profound conception of obedience to a stern and sovereign Absence that forged the fanatical energy for survival.

What was American Calvinism? An ‘authoritarian theology that stressed personal salvation through strenuous morality, righteousness over love and an autocratic governing principle over liberty’. It doesn’t sound like a legacy we would want to embrace, but it ‘produced brilliant, idealistic intellects. Most broke down in some way under the strain of worldly ambition that clashed with morbid fear and merciless introspection.’

It’s this ‘merciless introspection’ under duress that produced writers; writers produce antinomians; antinomians produce poets. Howe’s New England is a crucible of philosophy and theodicy, ambition and self-coruscation and frugality. One need look no further than the arresting juxtaposition of epigraphs with which she begins The Birth-Mark (1993), her critical study of early American literature. A passage from Hawthorne’s short story about facial disfigurement (‘The Birth-Mark’) is placed next to a quotation from one of Dickinson’s dash-ridden Master Letters and an excerpt from Melville’s Billy Budd, whose ‘vocal defect’, a stutter, is the only blight on the ‘Handsome Sailor’s’ beauty. This suggestion that stutters and birthmarks are a defining feature of the newborn country cuts two ways. ‘I share this screwed-up magpie ambivalence,’ Howe admits. ‘I mean, I am an Americanist. There’s something that we do, a Romantic, utopian ideal of poetry as revelation at the same instant it’s a fall into fracture and trespass.’

Reading the work that Howe has produced over the past half century, one marvels at the consistency and depth of her inquiry. If much of her writing sounds like the apotheosis of Eliotic impersonality, it’s surprising, and moving, when she allows the home lights to glow through the thickets. The history of Puritan New England is her history, through her father, Mark De Wolfe Howe – Boston Brahmin, Harvard law professor and the biographer of Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, for whom he clerked. De Wolfe Howe wrote a book on constitutional law called The Garden and the Wilderness, from which his daughter might have derived her guiding metaphor. (She would use his first name, the name she also gave her son, as a double entendre for her life’s work: making marks on paper.)

De Wolfe Howe married Mary Manning, a playwright and actor from Dublin, in 1935. (They had three daughters, two of whom became writers: Susan and her younger sister Fanny.) Manning’s influence can be felt in the early work collected in The Europe of Trusts (2002). The book opens with Susan recalling her return to the United States after a childhood visit to Ireland in 1938, travelling on a ship ‘crowded with refugees fleeing various countries in Europe’. In the same volume, a sequence called ‘The Liberties’ about the mysterious relationship between Jonathan Swift and his ‘Stella’, Hester Johnson, reads like the script of a play – a legacy of Howe’s year-long apprenticeship at the Gate Theatre in Dublin when she was in her late teens and considering following in her mother’s footsteps.

Two of Howe’s books are dedicated to husbands who left her widowed: Pierce-Arrow (1999), for the sculptor David von Schlegell, and That This (2010), for the philosopher Peter H. Hare. Nothing in Howe’s work exceeds the sheer beauty of the sequence ‘Rückenfigur’ – an art history term for a figure seen from the back – in Pierce-Arrow. It begins: ‘Iseult stands at Tintagel/on the mid stairs between/light and dark symbolism.’ It ends with an allusion to Stevens’s ‘wide water without sound’ from ‘Sunday Morning’ fusing it with her own Long Island Sound:

Day binds the wide Sound

Bitter sound as truth is

silent as silent tomorrow

Motif of retreating figure

arrayed beyond expression

huddled unintelligible air

Theomimesis divinity message

I have loved come veiling

Lyrist come veil come lure…

Lyric over us love unclothe

Never forever whoso move

There is an inescapable austerity to Howe’s lyricism – a Puritan insistence on abstraction, a poetry without ligatures, even as the elegiac tone grows stronger over the books of the last decade. Concordance (2020) includes a sequence called ‘Since’, an appropriation of Dickinson’s suggestion, in a letter to Judge Lord, that Shakespeare could have been even pithier: ‘Antony’s remark to a friend, “since Cleopatra died”, is said to be the saddest ever lain in Language – That engulfing “Since”.’

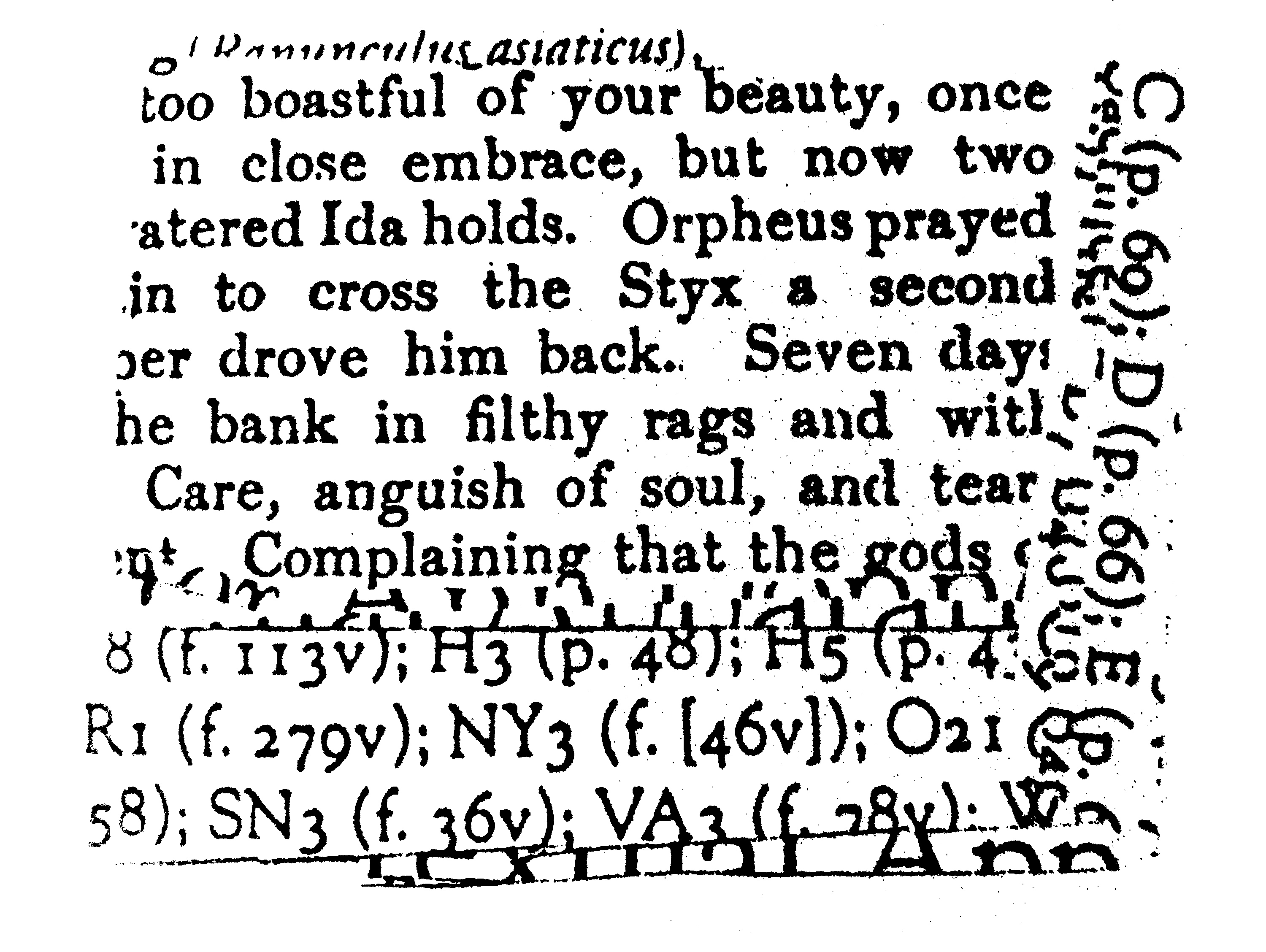

Penitential Cries is the latest instalment in what has become a prolonged epic. Its biblical title, its epigraph (Hosea 13:3), its stark opening (‘Each morning rapid heartbeat. Scattered alphabet’) and its motif of ‘widows and pariahs’ all build to a mood of foreboding. Death is closer than ever before. ‘Hush Angel of Revelation, brandishing a sword in right hand striding across myriad minimum long gone pension funds.’ Guardian L’Ange Heurtebise, from Jean Cocteau’s Orphée (1950), makes an appearance; Handel’s music ushers in the doomed Semele. Ghosts from Howe’s past work are as real as anyone she knew in life: Sarah Pierpont Edwards, wife of Jonathan; John Donne; Lear’s Cordelia. ‘Sterling Park in the Dark’, a set of collages that feature Orpheus and the River Styx, confirm the sense that Howe’s method is a kind of mediumship. The cryptic numbers – some kind of citation – seem to stand for the unexplained numbers broadcast by Orpheus’ underworld radio in Cocteau’s film:

Fanny Howe died in July. She played the spirited, rebellious Baby Sister to Susan’s patrician, above-the-fray Oldest Daughter; they dealt with their common legacy in different ways, and kept a distance from each other in print. Penitential Cries ends with Susan’s elegy for Fanny, a set of mostly dimeter couplets that seem to reference her sister’s apophatic work (‘No more doubt/Astonishing!’) and a penitential cry of her own: ‘On the subject/of assurance//I should have/I should have.’ The poem is called ‘Chipping Sparrow’, a dainty North American species on the small side, lovable and friendly. Yet I can’t help but hear ‘sorrow’ in ‘sparrow’, and of course ‘to chip’ is to break off. Susan Howe is still fiercely shoring her fragments.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!