The world you see depends on where you start from. Imagine that the centre of the known universe is the Milwaukee-Chicago corridor, on the shores of Lake Michigan, once the heartland and crossroads of American farming and industry: Wisconsin’s vast dairy herds to the west, Flint and Detroit’s clanking automotive plants and steelworks to the east. Railroads radiate from the Chicago switchyards to deliver cargoes across the continental United States, as far as the Atlantic gateways of Philadelphia and New York, the gulf ports at Houston and New Orleans, San Francisco for shipping to Pacific markets. Freighters, schooners, whaleback steamers carry lumber, grain, coal and iron ore across the Great Lakes, with fleets of trap-net fish tugs operating out of Sheboygan further up the shore. From this originary powerhouse, the rest of the planet can seem very distant.

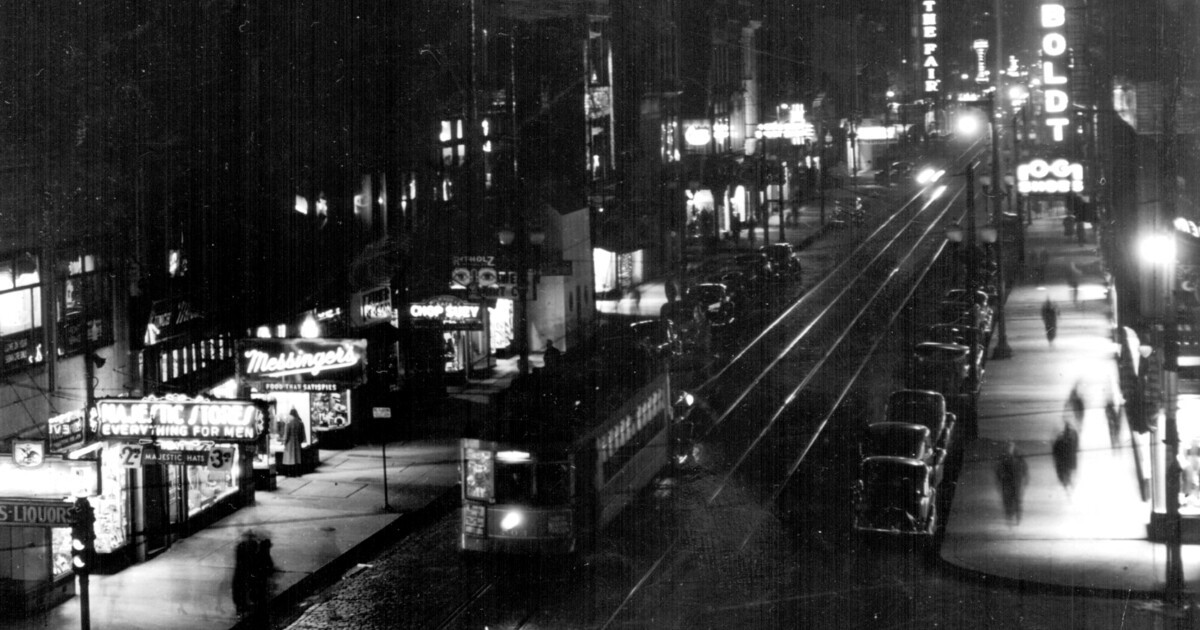

In his new novel, Thomas Pynchon also puts us at a particular point in time: 1932. It’s the middle of the Great Depression – strike-breakers hired to bust heads at union marches, anarchist actions against the police, inter-mob violence – but depressing is the last thing you would call this scene. Milwaukee is a riot of colour and sound, of dancefloors and speakeasies and good times being had. Prohibition on the way out, big-band jazz on the way in, and everyone on the hustle. The Aragon Ballroom in Uptown Chicago has ‘cork, felt, and spring-cushioned floor, palm trees, archways, tile, the Spanish courtyard treatment’; if you want something a little less sedate, you can head a few blocks south to a place where ‘the music is closer to jazz and the dancing experimental as anything in town’ – the Lindy Hop, the Half and Half. Or there’s Arleen’s Orchid Lounge in Milwaukee, where musicians from Bennie Moten’s band drop in after midnight with banjo-uke and sax, and the young Count Basie plays ‘Rumba Negro’ on the piano. There are other joints too: the Flame, the Polka Dot, the Moonglow and a fancy new blue-lit bowling alley with pool tables, pinball machines and Skee-Ball in the lounge area. Cocaine and Old Fashioneds plentifully on offer. Why would you ever want to leave?

The protagonist of Shadow Ticket is Hicks McTaggart, tough-guy strike-breaker turned private eye, and these are his streets: ‘half a tankful’s driving radius’ is as far as he’ll willingly go. He’s a detective of the Raymond Chandler type, with a touch of Bogart’s class – he once had a fling with Daphne Airmont, heiress to the Airmont cheese fortune. He’s wisecracking, fast-talking, like everyone in this place. Here he is with April Randazzo, nightclub crooner, a few dances in: ‘Oh my! Is that for me?’ April says. ‘Thought you’d never notice,’ says Hicks. ‘Maybe it’s the time of night a girl needs something to hold on to.’ ‘Go ahead, it won’t mind.’ But his day job is at U-Ops, a detective agency specialising in ‘wandering spouses, beer-related intrigue, a little freelancing whenever the Outfit shows up needing some cheap labour’. Al Capone is in the federal penitentiary down in Atlanta but his associates are still known to whip out their tommy guns when provoked, and they may or may not be behind the bomb that gets rolled under Stuffy Keegan’s hooch wagon one fine day. But they can be friendly enough, at least with a guy like Hicks, who’s happy shooting the breeze with an old goombah like Lino ‘the Dump Truck’ Trapanese, who offers him ‘un piccolo consiglio’ whenever they run into each other in Bronzeville.

An explosive device of unknown provenance is enough to set a plot in motion, especially when it coincides with Hicks’s other mission – to locate Daphne, who is thought to have absconded with a clarinet player in a swing band. It’s classic caper-ville: a Some Like It Hot set-up, complete with a contraband-running REO Speed Wagon pursued by cops, bass players desperate for a gig and Sicilian consiglieri in tailored suits threatening muscle. But it’s not all effervescence, and mobsters aren’t the only antagonists. Being the centre of the known universe, this place is also a magnet, drawing in chancers and grifters from all over the globe: Polish longshoremen loading cargo in Milwaukee’s Third Ward, Chinese 0pium-peddlers working off 2nd Street in Chicago, German butchers, bakers and cabinet-makers plying their trade on the North Side. There’s an underworld here, and Hicks has seen it all, picking up tips from ‘drifters, truants and guttersnipes, newsboys at every corner and streetcar stop’. In the ballrooms and cocktail lounges of the swish parts of town we’re with Billy Wilder; out on the streets it’s The Threepenny Opera, with Macheaths round every corner.

There’s no haunt or hangout Hicks won’t enter. Following leads means visiting the domain of each of Milwaukee’s citizenries in turn, and each is a world unto itself. He shares Mistletoe gin with the grizzled old-timers of the Milwaukee PD, who’ve been keeping their circle tight (‘There are things we can’t share with any civilian’) ever since a bomb blew up the station house in 1917. He calls on the radio hams and physics whizzes who’ve clandestinely wired up a warehouse under the Holton Street Viaduct to monitor cop traffic and shipping transmissions for information that can be sold on. Hicks’s Uncle Lefty, an ex-cop intimate with the complexities of German American politics, introduces him to the New Nuremberg Lanes, which – rather than a regular bowling alley – turns out to be a meeting place for well-dressed admirers of the man the Milwaukee Journal recently called ‘that intelligent young German Fascist’. Hicks gets told to relax: ‘We’re National Socialists, ain’t it? So – we’re socialising. Try it, you might have fun.’ Every secret society in this town, every gang or faction, has its own codes and rituals, its own argot, its own laws of omertà.

But which of these shadowy networks is really running the show? Hicks gets a clue when he pays a visit to Hoagie Hivnak, proprietor of the Ideal Pharmacy, which (like many drugstores in the US at the time) serves sundaes and other soda fountain treats. In exchange for a $2 bill, Hoagie tells Hicks there’s no way the bomb that took out Stuffy’s truck was a ‘goombah grenade’ – or even, as the MPD hypothesise, a ‘precision-engineered, custom-built’ device of German origin. In fact, Hoagie says, Hicks should be looking at his own ‘all-American type of neighbourhood’, and here’s why:

Spend your whole day around ice cream, you can begin to grow philosophical. You figure a state with two million dairy cows, a certain per cent of that milk will be going into ice cream, nickel a cone, been that way for ever. But it turns out there’s milk and then there’s milk. The kind you drink from a bottle is more expensive than the kind they use to make butter and cheese and ice cream out of. A two-price system is what they call it. Now we got syndicates of Bolshevik farmers looking to make it all one price, meaning the cost per scoop of ice cream goes up 70, 80 per cent, next thing we’re looking at a dime cone, the banana split you thought you wanted goes up to 30, 40, 50 cents, no end in sight.

Nothing could be more all-American than milk. But in Wisconsin, America’s Dairyland, milk was money. Those two million dairy cows pumped out enough to fill two billion pint bottles a year, and in 1932, Wisconsin accounted for half of all US cheese production, with a great proportion of it controlled by a single company, Kraft. So it makes sense, in Pynchonworld, that behind everything must be a vast cheese conspiracy, a secretive cabal of unknown reach and power.

Daphne’s father, Bruno Airmont, known locally as the Al Capone of cheese, built a fortune before coming under federal investigation – there’s a paper trail of ‘dummy corporation records, lawsuit summaries, dishonoured cheques, rap sheets and police reports’ – and skipping the country. He’s supposed to have retired to ‘some remote tropical island nobody’s sure which, drinkin’ Singapore Slings out of a fire hose’ – but it’s hard not to suspect his hidden hand, or the hand of the organisation he works for, behind any number of unexplained events. So, unfortunately for Hicks, the hunt for Bruno Airmont has to be added to the job ticket, which just keeps getting longer.

Does this all sound like one big cheesy joke? It is, and Pynchon piles it on. During the Cheese Corridor Incursion of 1930, he tells us, agitators were knocking over ‘truckloads of case-hardened palookas’, ‘tossing provolones back and forth like footballs, rolling along the ground giant waxed wheels of domestic Parmesan’, with ‘bricks of Brick wrapped in tin-foil and carried away by the hodful’. But the milk wars were real, and Hoagie has it right: in 1933, dairy farming co-operatives went on strike – stopping milk trucks at picket lines, vandalising creameries and cheese factories – to demand minimum prices from corporate distributors and producers. Eventually, the state governor called in the National Guard.

And sometimes reality is just as wild as Pynchon’s exuberant imagination, as Ian Hamilton discovered while trying to write the biography of another famously elusive American author. Since J.D. Salinger, like Pynchon, refused all interviews, made no public appearances and was barely ever caught on camera, he was hardly likely to co-operate with a biographer. So in order to write the book that eventually became In Search of J.D. Salinger (1988), Hamilton had to work the streets. He paid visits to the cheesemen of New York, mostly Italians ‘almost mafialike in their suspiciousness’, in the hope that they could tell him something about Salinger’s father, Sol, who had worked for a Chicago cheese firm called J.S. Hoffman and Co. This led to an interesting discovery: ‘In 1941 the FBI seized 32 cases of Hoffman’s Sliced Wisconsin on the charge that it contained “faked holes”.’ So you thought the cheese world wasn’t shady?

Pynchon thrives on connections like these: he’ll follow them wherever they go, and beyond. A working stiff like Hicks, for whom the streets of Milwaukee are world enough, may be more reluctant. He’s not delighted when his boss hands him a one-way ticket to New York, funded by parties unknown, and tells him to get the hell out before he gets into any more trouble. In New York, it takes more than the offer of an advance on two weeks’ pay and a steamer ticket, handed to him by a clerk in a branch of Gould Fisk Fidelity Bank and Trust, to get him even to consider leaving American shores in pursuit of the missing heiress. When he wakes up to find himself on board the ocean liner Stupendica it’s only because last night’s beer had been pepped up with ‘something in the chloral hydrate family’.

We’re pretty much halfway through the book. Part One: from Sheboygan down as far as the Chicago Loop. Part Two: Belgrade, Budapest, Geneva, Vienna, Bratislava, Hamburg, Fiume. The motherlode of the American Midwest on the one hand, the seething ferment of Central Europe on the other, caught at a moment between two cataclysms: the postwar Treaty of Trianon, which tore apart Hungary and handed over some of its people to Romania, Czechoslovakia and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes; and the war of extermination to come. But just as you can map every street corner of downtown Milwaukee, so you can pinpoint each node of Europe’s tangled political web. Or the places where forces converge. Hamburg, where brownshirts sing Nazi lyrics to the ‘Internationale’ while dockworkers try to drown them out. Bratislava, formerly Pozsony, formerly Pressburg, where Jews are arming themselves against the Czechoslovak Legion. And a significant hinge point, Fiume, or Rijeka to the Croats: once Hungary’s only access to the sea, now contested between Italy and Yugoslavia, ‘partitioned, variously occupied, paperwork, bribery and larceny everywhere’.

None of this means you can’t still have a good time. Especially at the Tropikus nightclub in Budapest, a nautical-themed all-night cabaret, where ‘waitresses in abbreviated sailor-girl get-ups’ hand out fruit-heavy cocktails in coconut and conch shells. And it’s here, to a Latin American accompaniment of claves, timbales and cowbells, that Hicks finally catches up with Daphne Airmont. ‘Go on ahead, tough guy, what’re you waiting for?’ she says. ‘Slap on those cuffs and bring me on back to the USA.’ Except the USA is a long way away and not really on anyone’s mind. A gumshoe in Milwaukee follows leads, picks up his girl and collects his pay packet. On Nagymező utca, the ‘Broadway of Budapest’, he’s more likely to accept an invitation to her fancy hotel and see where that leads him. In a Europe where it’s all happening, everyone is always on the move, and whatever city you land in always has another palace of music and dance to haunt your dreams:

At Night of the World, inspired by the multi-floor cabarets of Berlin, what circles of depravity may be found do not rise from street level but instead go corkscrewing down beneath it, ten floors down it’s said, ten known of and more rumoured, down through boiling mineral springs, towards ancient depths few have been willing to dare, each with its own bar and dance band and clientele.

This isn’t a vision of Inferno: there’s no place for that in Pynchon, no judgment, no damnation. But it’s a useful picture of the way his world works. There are circles everywhere to which people may belong. As in Milwaukee, with its secret fraternities of Italians, Germans and Poles, there are underground tribes operating across this fractured stretch of Europe. In Budapest, Hicks is introduced to Terike, a dispatch rider, and initiated into what turns out to be a vast confraternity of motorcycle enthusiasts who zip through limestone tunnels under the city and out over the mountains in pursuit of their mission. ‘Some riders are here on intelligence-gathering operations, reconnaissance, mapping, some are zealots’ – but they all share a code of honour and coolness under fire. They also take part in an annual race, the Trans-Trianon 2000, a circuit through Transylvania – sometimes called ‘Hungary Unredeemed’, lands lost under the treaty that divided the country. Or there are the apportists, a band of psychics who share the useful ability to make an object vanish and reappear somewhere else entirely, a skill that is valued alike by jewel thieves, searchers for stolen goods and a branch of Soviet intelligence engaging in paranormal research somewhere in the Russian Far East.

These sects, each with its own agenda, are inscrutable to the uninitiated, like the clandestine outfits that may or may not be controlling events in so many of Pynchon’s novels, from the Trystero of The Crying of Lot 49 to the Schwarzkommando of Gravity’s Rainbow to the Golden Fang of Inherent Vice to the Chums of Chance of Against the Day. In the 1930s Europe of Shadow Ticket, they are just part of the circuitry, no more outlandish than any of the spies, adventurers and agents provocateurs who criss-cross the continent. Those are in the book too: Alf and Pip Quarrender, whom Hicks meets on the boat, British intelligence agents with an eye on the Soviets; Egon Praediger, head of Croatian affairs at Interpol in Vienna, with a side interest in dealing cocaine; and ‘Nigel’, who while working as a musicians’ booking agent from a low-rent office in Geneva is also planning the infrastructure for Jewish resistance to the Nazis – ‘exit routes, dummy post office boxes like those already in Lisbon and Shanghai, fuel dumps, secure places to sleep’.

In this international game of intrigue, the mission Hicks thinks he’s on keeps changing. He’s flicked around Europe like a pinball: X sends him after Y, who sends him after Z; in constant motion like everyone else in the book, he travels on trains, boats, road Pullmans, motorbikes, a submarine. But there are certain places where the same people keep colliding. Maybe these are just natural intersections on the map, or maybe there’s more to it: in the disturbed fabric of European spacetime, the tiniest crack may inescapably pull you in. Deep in the Transylvanian forest, somewhere on the route of the bikers’ circuit, he arrives at a large parts depot surrounded by ‘roadside taverns, overnight flophouses, fuel stations, eateries, repair shops’, a little city in itself. He hears music drifting out of a cabin – ‘“Star of the County Down”, a longtime favourite of Irish drinkers he’s known’ – and who should be sitting at the piano but Pip Quarrender, looking a little glum. They exchange a few friendly words before he heads off again for his next stop, making sure to avoid the Ustaše-run terrorist training camp on the Hungarian-Croatian border.

But all roads eventually lead to Fiume. Once, it was the main port of departure for Austro-Hungarians emigrating to New York, tens of thousands of them a year travelling on Cunard liners. It was a vibrant mixed city of Italians, Croats and Hungarians which handled the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s trade with the Levant and the Black Sea. But then the tussles began, with treaties and backroom deals: wrested from Hungary, seized by Italy, declared a Free State and, by 1932, again under the control of Fascist Italy, the city is ‘barricaded and wire-fenced, corroded, sentry-boxed’ against the Yugoslavs. It’s here, it turns out, that the elusive Bruno Airmont decided to acquire a villa, conveniently giving out his address as ‘Currently in Dispute’. And, appropriately, it’s where everyone in the book somehow ends up: Hicks, Bruno, Daphne, Terike the dispatch rider, Dr Zoltán von Kiss the apportist, Porfirio del Vasto the jewel thief, Ace Lomax the hired gun and – out of nowhere – Dippy Chazz, a gangland acquaintance of Hicks’s from Milwaukee, a place that from this vantage point on the Adriatic has become quite hard to imagine.

The universe has no centre. What Pynchon has mapped is a world that is continuous and connected, where borders, however securitised, are porous. Drop a pin on the map, anywhere on the map, and that’s your point of origin, from which everything flows. Milwaukee, the factory on Juneau Avenue: origin of the Harley-Davidson Flatheads that are driven over the Carpathian mountains by Hungarian motorcycle fiends. Fiume, the Whitehead Torpedo Factory: origin of the self-propelled torpedoes that armed the US navy. Pynchon shows the way ripples from the political earthquake in Berlin are felt in the bowling alleys of Milwaukee, and the music sung in a Chicago cocktail lounge is received and remodulated in a nightclub on the Danube.

What’s unfathomable is how he does it: wherever Pynchon drops his pin, he seems to know the place, and the time, in every detail, with street-level precision. How does he know that if a detective in Chicago in 1932 pulls a bottle out of his desk drawer it’s going to be a pint of Old Log Cabin, but that if he’s in Milwaukee it’ll be Korbel brandy? How does he have time to learn about the Milwaukeean shoe stores that used fluoroscopes to X-ray a customer’s foot for the perfect fit? I wish I could see his library. I imagine shelf after shelf devoted to early studies of Central Europe, beginning with Paget’s Hungary and Transylvania; with Remarks on Their Condition (1839). I imagine tabulated volumes on Wisconsin milk production, boxfuls of issues of the Milwaukee Journal from the 1930s, playbills, flyers, stacks of faded photographs of movie palaces and ballrooms. And that’s not to mention his record collection, which seems to include performances by every known vocalist or band member who passed through Milwaukee and Chicago at the time. All on the original shellac?

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!