‘Teresa Guiccioli’ by Henry William Pickersgill.

Teresa Gamba Ghiselli married Count Alessandro Guiccioli in 1818. She was 18 or 19; he was 57. It was his third marriage and they had met once before. In The Last Attachment: The Story of Byron and Teresa Guiccioli (1949), Iris Origo describes how the bargain was struck:

[Teresa] stood in the middle of the room, curtsying, as her father introduced her to a rigid elderly man with red hair and whiskers, whom she had never seen before. The room was ill-lit, and the future bridegroom was short-sighted. Without a word, he took a candle in his hand, and with a faint smile on his thin lips he slowly walked round the girl, examining her points ‘as if about to buy a piece of furniture’.

Guiccioli was one of the foremost men of Ravenna, the owner of a fine palace, a country house, a coach-and-six and a box at the opera. He was also rumoured to have had two of his enemies assassinated and to have poisoned his first wife, after tiring of her protests about illegitimate children. Teresa, the daughter of another Ravenna nobleman, Count Ruggiero Gamba, was newly out of convent school, where she had received an unusually enlightened education and read widely. When she encountered Lord Byron at a conversazione in Venice in April 1819, she was feeling trapped in her marriage and open to ways out.

Byron had lived in Venice since 1816, the year of his departure from England. Even for him it had been a ‘spectacularly undomestic’ period, involving a succession of fiery Italian mistresses and much of what he called ‘fuff-fuff and passades’. After the conversazione, Teresa reported that they began meeting in secret: ‘I was strong enough to resist at that first encounter, but was so imprudent as to repeat it the next day, when my strength gave way.’ Her infatuation was immediate, but the surprise was Byron’s, which crept up on him despite his firm resolution not ‘to love any more’. Ten days into their affair, when Guiccioli announced to his wife that they were leaving, he took the extraordinary step of promising to follow them to Ravenna.

Byron had previously been scornful of the Italian convention of cavalier serventismo, by which women in marriages of convenience took subservient male lovers, usually in the knowledge of their husbands, whose office it was to hand them into carriages and accompany them to the theatre. (‘As to the love and the Cavaliership I was quite of accord, but as to the servitude it would not suit me at all,’ he told his half-sister, Augusta, in 1816.) But in Ravenna, where he spent the summer of 1819, he found himself sliding into the role: hovering anxiously by Teresa’s bedside during an illness, riding with her daily in the pine forest. When the Guicciolis travelled to Bologna in August, the count accommodated Byron in his own residence; the following month, on the pretext of consulting a famous physician, the lovers disappeared to Venice while Guiccioli remained behind.

A locket containing Byron’s hair.

Almost everyone was against the relationship. Venetian society, which had ‘tolerated all Byron’s previous sordid adventures’, could not countenance a proper romance: ‘Till this unfortunate affair he conducted himself so well!’ a contessa exclaimed to Thomas Moore. Pietro Gamba, Teresa’s brother, wrote to warn her that Byron was believed to keep his estranged wife ‘shut up in a castle, of which many dark mysterious tales are told’ and had once ‘been a pirate’. Guiccioli himself, who had so far turned a blind eye, finally lost his temper in November 1819 and issued his wife with a set of conjugal rules, which ranged from the practical (‘1. Let her not be late in rising, nor slow over her dressing’) to the pointed and sinister (‘10. Let her receive as few visitors as possible’; ‘17. How can she always be completely sincere with her husband with this worm gnawing at her heart?’). Teresa, uncowed, retaliated with a set of ‘CLAUSES IN REPLY TO YOURS’ – ‘1. To get up whenever I like’; ‘2. Of my toilette I will not speak’ – and refused to stop seeing her lover. On Christmas Eve, Byron followed the Guicciolis back to Ravenna and stayed there. ‘Love has won,’ he wrote to Teresa. ‘I shall return – and do – and be – what you wish.’ Teresa considered it only right: ‘It is hard that I should be the only woman in Romagna who is not to have her Amico.’

‘To go to Cuckold a Papal Count, who, like Candide, has already been “the death of two men, one of whom was a priest”, in his own house, is rather too much for my modesty,’ Byron had written to Richard Hoppner, the British consul, earlier in the year. But that was exactly what he proceeded to do. Palazzo Guiccioli, the count’s elegant neoclassical residence in the heart of the city, became his home until he left for Pisa in October 1821. In February 1820, at Guiccioli’s somewhat surprising suggestion, he moved in, taking over the first floor while husband and wife occupied the ground level. In July, when a papal decree granted Teresa permission to leave her husband and return to her father’s house, he remained, ignoring the count’s notice to quit. Since 2024, the palazzo has housed the Museo Byron, a commemoration of his life and work, centred on meaningful objects treasured up by Teresa during their years together and after his death.

The basket in which Teresa kept Byron’s letters.

There are his letters to her, which Teresa kept in an 18th-century basket inlaid with her father-in-law’s coat of arms (as if no Guiccioli could be safe from Byronic infiltration). A handful of dried leaves and fruits and a fern branch represent a pilgrimage she made to Newstead Abbey, Byron’s ancestral home, in 1857, when she was almost sixty. There is a brittle, heavily crinkled rectangle of cloth with a stain, marked: ‘This handkerchief belonged to Lord Byron and never left me during the illness I was struck by because of the sorrow of leaving Lord Byron in Venice.’

Among the more anatomical relics are a collection of desiccated, semi-transparent flakes in a Petri dish (described as ‘Skin of L. Byron fallen from him in an illness caught from swimming for three consecutive hours under the blazing rays of the August sun in the year 1822’), and a series of coils of hair: a lock of Byron’s cut in Tuscany in 1822; another tinged with white, taken ‘after his death’; two locks twisted together, ‘L.B.’s and T.G.G.’s Hairs’. A curly little auburn clump, which looks distinctly pubic, has the coy curatorial note ‘body hair’, though in Teresa’s handwriting, below the words ‘Di Lord Bÿron’, there is an expressive ‘?’.

The Museo Byron is an untraditional literary house museum because it gives little space to what Byron did within the palace walls. One room, ‘In Ravenna’, describes aspects of his life in situ. In the others, interactive displays and digital projections recreate his time in Venice and Greece, his love affairs, his famous works and characters and his posthumous celebrity. The result is that a burning question goes largely unanswered. What must it have been like to live cheek by jowl with the man you’d cuckolded? In the early 19th century, for a woman’s cavalier servente to occupy the same household as her husband was not uncommon, but Byron wasn’t your average cavalier. With him came his three-year-old daughter Allegra, a retinue of servants and a veritable zoo of animals he’d acquired during his years in Italy: dogs, cats, horses, monkeys, a fox, a peacock, a hawk, at least one goat, guinea-hens, a crow, an Egyptian crane. The crow in particular seems to have been a liability, regularly showing up in the pages of his Ravenna diary: ‘The crow is lame of a leg – wonder how it happened – some fool trod upon his toe, I suppose.’ ‘Fed the two cats, the hawk and the tame (but not tamed) crow.’ ‘Beat the crow for stealing the falcon’s victuals.’ Palazzo Guiccioli, Origo notes, ‘was in fact a not particularly spacious town house, with a single staircase’:

Here Byron, Guiccioli, Teresa and all their numerous servants – not to mention Allegra, the dogs, the cats, the monkey, the peacock, the guinea-hens and the Egyptian crane – must have met several times a day. Then they would retire to their separate apartments – the count and his wife quarrelling downstairs and Byron sulking upstairs.

Daily life was a combination of monastic literary labour, the provincial social round, and episodes of domestic hostility and intrigue. Byron worked through the night (Teresa encouraged his productivity), dined frugally (he liked the yolk of a raw egg for breakfast, taken in the early afternoon), and saw Teresa in secret and in the moments of public ceremony associated with serventismo, at conversazioni or the opera. When the lovers couldn’t meet, they communicated in notes, carried from one floor of the palace to the other by Teresa’s maid or a page. Almost from the start, Guiccioli seems to have taken a strange double attitude to their liaison. He subtly encouraged it as far as it allowed him to lean on Byron for money, but kept spies in the house to gather evidence against his wife. During the weeks leading up to their separation in 1820, eighteen of his servants – including the cook, the maids and two carpenters – were employed to listen at doors. That summer, when Teresa wasn’t supposed to be seeing Byron, Guiccioli’s spies reported secret rendezvous at the palace after dark, Teresa dressed in black or disguised as a servant. We can only imagine the atmosphere after she had returned to Palazzo Gamba but Byron continued to occupy the floor above his sworn enemy.

The cavalier existence, rule-bound and closely surveilled, was often dull. The ‘hot-blooded aristocratic rebel’ side of Byron, as the museum puts it, must have been frustrated. ‘I double a shawl with considerable alacrity; but have not yet arrived at the perfection of putting it on the right way,’ he wrote to John Cam Hobhouse of his duties in March 1820, adding: ‘Nobody has been stabbed this winter.’

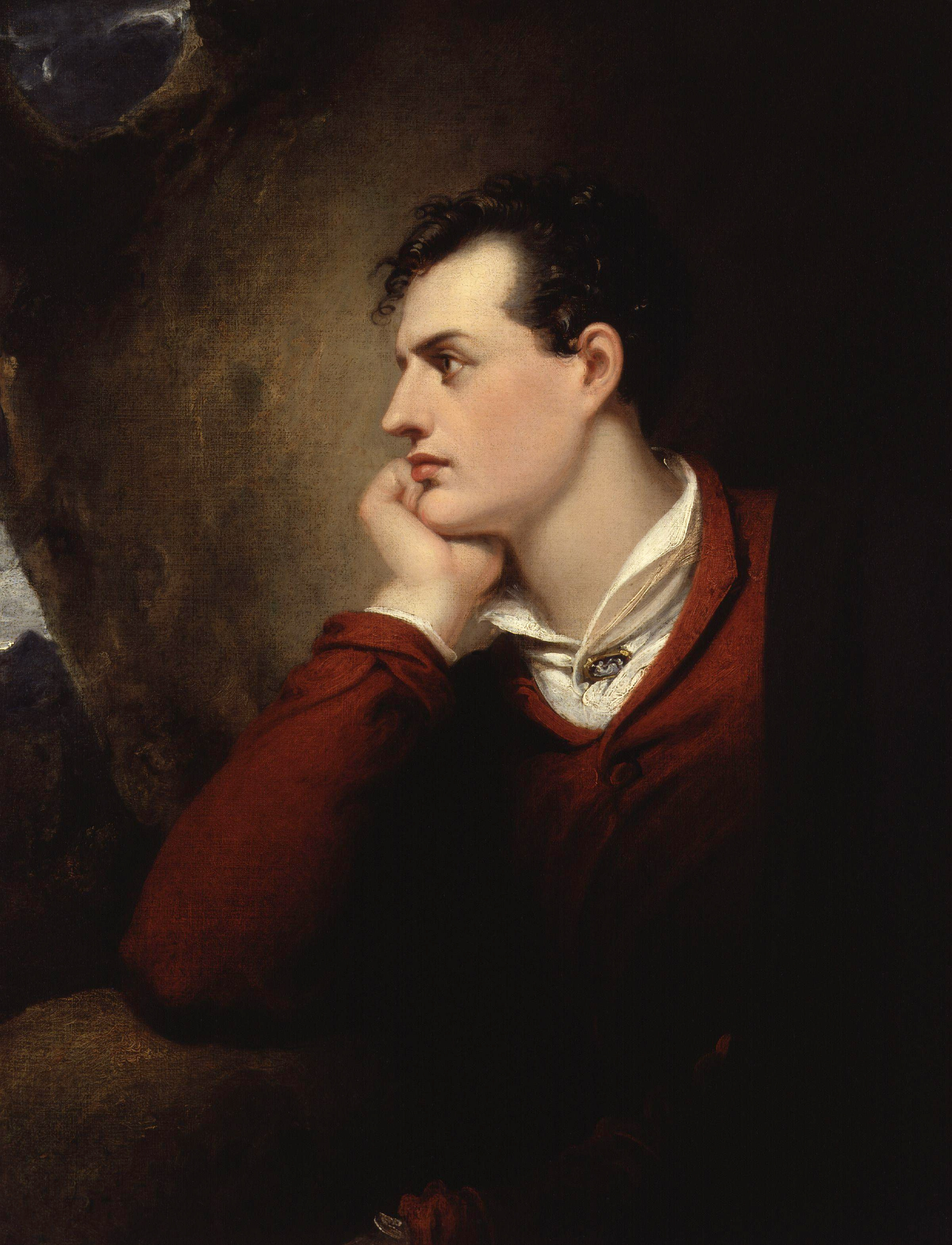

‘Lord Byron’ by Richard Westall (1813).

Things were different the following winter. After the Guicciolis’ separation, Byron grew close to Ruggiero and Pietro Gamba, who were key figures in the Romagna branch of the Carbonari, the underground revolutionary network that sought to overthrow Austrian and Bourbon rule in Italy. Enthused by their cause, Byron became the capo of a local band, which met secretly in the pine forest. He enjoyed the boyish conspiratorial side of things, the reconnoitres and intrigues, the whispered passwords: ‘The Count P.G. this evening … transmitted to me the new words for the next six months … The new sacred word is ***.’ In early 1821, when shots were fired in the streets and there was serious talk of a rising, he threw himself into insurrectionary organisation. Without Guiccioli’s permission and no doubt against his wishes (the count’s political connections were to the papal government), Palazzo Guiccioli became an unofficial rebel headquarters. Byron flew the Carbonari flag from his balcony, hosted meetings, bought and stockpiled an astonishing quantity of ‘bayonets, fusils, cartridges and what not’, and distributed money on the doorstep (funding sympathisers, Clara Tuite writes, became part of his ‘domestic economy’). His house, he told Pietro proprietorially, would do well in a siege: ‘I … offered, if any of [the rebels] are in immediate apprehension of arrest, to receive them in my house (which is defensible), and to defend them, with my servants and themselves (we have arms and ammunition) as long as we can.’

On the floor above the Museo Byron today is the Museo Risorgimento, which tells the story of the movement for Italian unification from the Napoleonic period to Garibaldi. One of its rooms, ‘Byron’s Study’, explains the poet’s role in the thwarted risings of 1821 and the importance of his works to later generations of Italian intellectuals and radicals. But in both museums more could be made of the major part that he played in Carbonari activities under the palace roof. ‘In Italy no matter is so personal that it does not become tinged with politics,’ Origo suggests, and Byron’s romance with Teresa was a threat to those who feared he might become a focal point for liberal opposition. The police read his letters and kept tabs on his movements (the commissioner in Volterra scanned an Italian translation of The Prophecy of Dante for clues that he sought to ‘augment popular agitation’); there were attempts to arrest and banish his servants; Guiccioli was enlisted to make an ugly scene and force Teresa to end the liaison. For a long time, Byron was defiant: ‘If they think to get rid of me they shan’t.’ What worked at last was a kind of pincer movement. In July 1821, Pietro and his father were arrested and sent into exile in Tuscany; shortly after, Teresa fled, in response to rumours that Guiccioli had asked the pope to pack her off to a convent. It was another three months before Byron finally had the grand rooms of the palace stripped, sent on his retinue and the zoo, archived his love letters, and departed for Pisa and his amica. He left behind only the animals he could not take with him – ‘a Goat with a broken leg’, ‘a Bird which would only eat fish’, ‘a Badger on a chain’ – in the care of his Ravenna banker.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!