Social Europe and the Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) of the Hans Böckler Stiftung are launching a new series on how Europe and Germany should respond to Trump’s divisive politics. The question is urgent: the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy represents nothing less than a declaration of economic and strategic war on the possibility of Europe emerging as a co-equal great power. In this opening essay, I analyse the competing strategies of the world’s major powers and argue that Britain’s political class must finally admit what the logic of events makes inevitable—that when forced to choose, Britain will choose Europe.

I have been to numerous defence and security-focused seminars since Donald Trump launched his National Security Strategy, and even two months later, I am still hearing people say: “I can’t work out what Trump wants and none of it makes sense…”

With events flowing thick and fast—from the seizure of Maduro, the crisis over Greenland and now a US armada off Iran—politicians and security analysts alike are rightly prudent when it comes to calibrating how bad things are. But the options are clear enough.

I am currently writing a new history of the League of Nations: the one-line summary of why it failed is that the authoritarians had a better theory of reality than the democrats. Lenin, Mussolini and, later, Stalin, Hitler and the Japanese militarists all had worldviews based on force, destiny and economics, while the liberal and conservative elites of Europe were operating with a mixture of illusions in international law, collective security and principle.

Smart, Progressive Thinking on the Big Issues of Our Time

Join 20,000+ informed readers worldwide who trust Social Europe for smart, progressive analysis of politics, economy, and society — free.

Put more simply: the authoritarians had theories of history—in which “laws” work behind the backs of rational agents. The democrats simply believed in intent.

Using that framework, I want to suggest that the options of the four potential great powers of the mid-21st century are essentially binary: each has an explicit theory of victory and an implicit theory of failure.

China’s rational gambit

China’s theory of reality is premised on its slow rise to dominance, becoming the strongest country on the planet in terms of national power by 2049. It does not need revolutions or collapses elsewhere to achieve this: Sinified Marxism under Xi Jinping is—as one of its supporters, the late Domenico Losurdo, pointed out—completely shorn of millenarianism. It sees state-run capitalism as the route to civilisational dominance and the 100-million-strong Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the voluntaristic force that will make this happen.

Its theory of victory is embodied in the massive buildup of People’s Liberation Army combat power, together with the New Quality Productive Forces (NQPF)—18 industrial sectors that do not currently exist, which China plans to dominate before the West can even make a start.

In Marxist theory, the development of the “productive forces” drives history to the point where the “relations of production” crack and give way to something else. My reading of Xi’s NQPF project is that he wishes to design a technologically driven economy which democratic liberalism cannot replicate. A good example would be the “low-altitude economy”—which sees the deregulation of airspace below, say, 500 feet, opening transport and sightseeing routes in the sky while Europe’s civil aviation regulators are still fretting about DJI quadcopters.

An implied Chinese theory of failure, therefore, would involve: internal social disorder and class struggle; regional breakup; effective military containment by the USA during its likely first gambit—the blockade and seizure of Taiwan; or failure to maintain decisive global technological leadership. While all of these are possible, they are all within the gift of the CCP to avoid.

China, in short, has a rational and plausible theory of the historical conjuncture.

Russia’s theory of reality is, by contrast, totally irrational. Its ruling elite believe they are destined to be a great power, despite having an economy the size of Italy’s and having pawned themselves to China during the four years of the war in Ukraine.

Putin’s theory of victory is to suppress Ukrainian national identity and to neutralise NATO, by staging an act of aggression that splits the alliance and proves Article V a dead letter. It is driven not by logic but by ethno-nationalist ideology. Putin’s concept of what happens if that fails is stark: it is the end of Russia—probably leading to breakup and regime change. “What is the point of the world without Russia in it” was, in this context, not a question but a threat.

The theory of reality embodied in Trump’s National Security Strategy, and the new National Defense Strategy issued by Pete Hegseth, can only be understood once it is rooted in political economy. That is why, to security professionals obsessed with force matrices and procurement schedules, it looks irrational.

The best explanation of Trump’s overall intent was summed up in a Rabobank note entitled “President Trumpachev/Gor-ump: Trump’s Reverse Perestroika”. In it, senior strategist Michael Every charts how the White House is currently trying to rewire American capitalism and, with it, the global economy. Trump is pursuing fiscal dominance—effectively curtailing the independence of the Federal Reserve and subordinating monetary policy to national security. He is pursuing neo-mercantilism—not only through tariffs on friend and foe alike, but through physical dominance of raw material supplies and choke points in the global supply system.

He envisions an American “Warsaw Pact” in which global south countries adopt development models dictated by the USA, funnelling their raw materials and manufactures into the global north on American terms, in return for American protection. Furthermore, he is implementing reverse capital controls, using trade deals to require weaker countries to channel their dollars as foreign direct investment into American sectors of the MAGA elite’s own choosing. And he is preserving dollar dominance by forcing countries to reduce their trade surpluses with the USA without ceasing to lend to the US Treasury and hold dollars. Stablecoin, as Every points out, is a vital weapon in this strategy.

The outcome, says Every, is that “countries that wish to access US markets will be forced to align their policies, and will benefit from lower US tariffs. Those who do not will face significantly higher US tariffs, and will be excluded from these integrated, upstream-to-downstream geopolitical supply chains and defence umbrellas.”

Like all other great power projects, there is a concomitant theory of failure: Trump’s project could fail (and my hunch is that it very likely will fail) because you cannot control capitalism. The AI bubble will burst, market forces will prove stronger than coercion when it comes to US Treasuries, and the growth expected from the tariffs imposed will be hard to achieve because all economies are “sticky” when it comes to incentives imposed by diktat.

But there are also geopolitical factors that could thwart Trump’s strategy. First, Europe could refuse to play ball. It could impose reciprocal tariffs, unify its military procurement pipelines and become strategically autonomous within the Western alliance. Second, China could refuse to accede to Trump’s offer to “maintain a balance of power in the Indo-Pacific that allows all of us to enjoy a decent peace”.

Europe’s narrow path

Now let us come to Europe: the Draghi Report spelled out the European theory of victory. Europe has to take off the fiscal brakes, rearm, deepen the single market and adopt a state-led, investment-driven growth strategy. If it does so it can – albeit reluctantly – play the new “great game” of power politics on at least an equal footing to the USA.

In a world where the rules-based order was still operative, this might have been achieved in collaboration with a Democratic-governed USA. Indeed, Brussels’ initial response to Bidenomics—collaboration on steel protectionism, for example—showed its willingness to do this.

But Trump’s National Security Strategy is a declaration of war on the possibility that Europe emerges as a co-equal great power. It is explicitly hostile to European liberalism and anti-fascism, and targets east and south European states for cultural-economic alliance with Washington, circumventing the EU.

The Trump strategy—rightly—pushes Europeans to fund and organise our own defence against Russia, but simultaneously identifies Russia as a threat “only” to Eastern Europe—not to NATO, the West and our collective security.

In response, I think it is likely that the major European states will begin to pursue more strongly what the Commission has called “open strategic autonomy”—at the level of military power, intelligence, energy security, information regulation and fiscal freedom of action.

The implied theory of failure for Europe is fragmentation: the fragmentation of European NATO under Russian pressure, and fragmentation of the EU under the pressure of the USA, Russia and China.

All of which frames Britain’s dilemma neatly. Britain’s strategy, for the 75 years since the formation of NATO, has been to keep the USA invested in the defence of Europe against Russia. In pursuit of this it has made its defence capabilities substantially dependent on those of the USA: its nuclear deterrent, its early warning systems and its strategic enablers are all provided by America.

Britain is fully invested—indeed more fully invested than almost any other major European power—in the defeat scenario for Russia. Britain has never been happy about the European strategic autonomy project as conceived by President Macron, but does not (under its current government) want the EU to fragment and fail. Britain appears to accept that China will rise peacefully to dominate Asia and perhaps the global south, but has tried to draw behavioural red lines in defence of its own interests.

As to the Trump project, Britain’s diplomatic elite have been painfully slow to understand what it is. They simply could not believe that the prime beneficiary of neoliberal globalisation, and the linchpin of the rules-based order, would be prepared simultaneously to rip both systems to pieces.

Now they must believe it, and that makes the UK’s dilemma acute.

It would, say experts, take a decade—and a dramatic switch to spending on rearmament—for European NATO to develop the strategic enablers that would allow it to defeat Russia without American assistance. So even if we start today, as envisaged with the SAFE mechanism, that is a decade of acute danger.

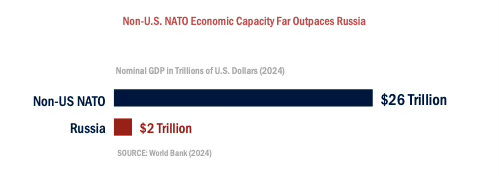

The chart in the US National Defense Strategy, showing non-US NATO countries’ GDP to be 12 times larger than Russia’s, is misleading. In the first place, it measures nominal GDP, not purchasing power parity; in the second place, non-US NATO defence spending is fragmentary. And it only matters if Europe starts spending on modernised defence capabilities, rapidly merges its procurement pipelines and adopts a force structure that convinces Russia that aggression will be both punished and denied.

So it is in Europe’s interest to keep the USA formally committed to the defence of Europe, and it is in Britain’s interest to go on helping Europe achieve that.

It is of course possible—with escalating effort—for Europe to keep Ukraine in the fight without American help. It would also be possible for Europe alone to defeat Russia in a war, especially the long war of attrition that Russia has chosen as its method against Ukraine. But it is not possible for European NATO on its own to deter a Russian attack between now and, say, 2030. For that, we need the USA.

The UK’s ideal outcome is in a space between the binaries: it needs to avoid European fragmentation but deter any kind of strategic autonomy from which it is excluded. It needs to stop Reverse Perestroika but avoid the collapse of America into an isolationist mess. And though it wants to see Russia defeated, it would settle for seeing it contained.

The problem is, history is driving the outcomes towards binaries and Britain must eventually choose. When it does so, the outcome is inevitable: it will choose Europe—and its political class need to admit that to themselves and get on with preparing for that moment.

It is in the UK’s interest for Europe to emerge as a co-equal player in great power competition—and for Britain to help lead that project, not watch from the sidelines. Everything in British foreign policy must flow from that recognition. Europe, for its part, must be ready to open the door: a Britain prepared to commit is an asset the continent cannot afford to turn away.

But very few of the outcomes lie decisively under the UK’s control. What we can control is the pace at which we rearm, the way we use power to soften the blows that are coming our way, and the extent to which our society coheres in the face of the disintegrating forces that are being unleashed within it.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!