ANALYSIS

As U.N. talks get underway, China is emerging as a key leader in international climate efforts. It is empowering the global energy transition, and along with India and Brazil, is becoming the driving force in climate diplomacy and filling a vacuum left by the world’s rich nations.

The U.N. climate conference opening this week was planned as the moment that each country would increase its ambition to meet the 2015 Paris Agreement target of limiting global average temperature rise to well below 2 degrees C. As delegates assemble for COP30 in Belém, on the edge of Brazil’s rainforest, the United States, a major player in the creation of that agreement, is leading an aggressive domestic and international campaign to obstruct further climate action.

China, meanwhile, still the world’s biggest emitter of greenhouse gases by volume and once the pariah of climate ambition, is staking its claim to leadership, both as the steady and reliable partner in the global energy transition and the primary purveyor of the means to achieve it.

COP30 in Belém may well be remembered as the moment that the world accepted the leading role of China in addressing humanity’s most important challenge.

The behavior of the U.S. delegation at a recent meeting in London to finalize an agreement on limiting emissions from maritime traffic is a further warning to delegates in Belém. U.S. threats to other delegations in London reportedly succeeded in stalling the formal acceptance of a global treaty that had already been agreed, after 10 hard years of effort. COP30 is billed as a meeting that aims to focus on implementation rather than negotiation, but similar U.S. interventions could still slow the global effort, just as science is warning that it needs to accelerate.

When the U.S. withdrew from the Paris Agreement, China’s position as the global supplier of low-carbon goods was unassailable.

In September, President Donald Trump told the U.N. General Assembly that climate change was a “con job.” The next day, China’s premier, Li Qiang, announced an emissions reduction target of 7 to 10 percent from an undefined “peak level” by 2035. The target falls far short of the Paris Agreement and is much less than China is already doing, but when the E.U.’s climate chief expressed his disappointment in the level of China’s ambition, China hit back.

“Some people turn a deaf ear and remain silent when hearing claims like ‘climate change is a hoax,’ but instead ignore and make irresponsible comments about China’s responsible and proactive actions to address climate change,” a Foreign Ministry spokesperson said in a written response.

For China, the target was a demonstration of its commitment to multilateral climate action and a further element in a claim to leadership that can no longer be dismissed. It was also a demonstration of the well-known Chinese preference to set low targets and meet them early, rather than failing to meet a more demanding promise.

Since the adoption of the first U.N. climate agreement in 1992, the countries of the European Union have played a leading role in shaping and driving global climate policy, but now the E.U. is beset by internal problems. Its primary industrial economy, Germany, is suffering from Chinese competition, and with the rise of right-wing parties, resistance has emerged to the ambitious climate policies of the European Commission. One symptom of these internal troubles was the E.U.’s embarrassing failure to agree its own mitigation targets before the informal deadline of September 30.

There are many ways to judge climate leadership: They include the quality and consistency of policy, the speed and effectiveness of carbon reduction, and the role a country plays in the global effort, including in support to less developed countries. China’s record on mitigation and international support is mixed at best, but its claim to leadership today has benefited from the actions of the U.S., the distraction of the E.U., and China’s own long-term, consistent, all-of-government approach.

When Trump returned to the White House in 2025, China had long been preparing for what it saw as an inevitable geopolitical confrontation with the U.S., a standoff in which climate is now an arena of ideological competition rather than cooperation. When China became the biggest carbon emitter by volume in 2005, its leadership did not contest the science. Importantly, they understood climate change as a severe threat but also as an enormous industrial opportunity. If the world needed to transition away from fossil fuels and towards clean energy, China resolved to be the supplier of the enabling goods and technologies.

China aligned its policies and industrial strategy accordingly: It slowly developed domestic policies to support its own mitigation and, critically, upgraded its economy by investing in the full range of technologies and supply chains that would be needed to achieve a global energy transition.

China is helping enable the energy transition, while the U.S. tries to force countries to buy U.S. oil and gas. Global trends favor China.

When the U.S. withdrew from the Paris Agreement for the second time, China’s position as the global supplier of low-carbon goods was all but unassailable. Last year, the country that carried much of the blame for the failure of 2009’s COP15 in Copenhagen, installed more renewable energy capacity than the rest of the world combined.

China today produces about 80 percent of all solar panels and more than 70 percent of all electric vehicles. It has also — by dint of subsidies, efficiencies, and economies of scale — brought down the cost of solar panels by almost 90 percent, reducing the overall capital expenditure costs for renewable projects by 70 percent, thus lowering, if not removing, the cost barrier to the energy transition for the rest of the world. China’s overwhelming industrial capacity in clean technologies now threatens what remains of similar capacity in other nations.

China’s ambitions go well beyond its own borders. The country that was once the biggest promoter of overseas coal projects announced an end to that policy in 2021 with a speech by Xi Jinping to the United Nations. He also promised to help developing countries with their energy transition. Since then, China has turned to clean technology exports and, perhaps in anticipation of future barriers to trade, to building clean energy factories abroad, investing in clean technologies in 54 countries since 2022.

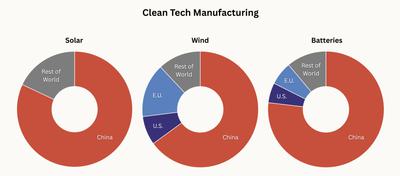

Share of solar cell, wind nacelle, and battery cell manufacturing capacity in 2023. Source: IEA.Yale Environment 360

In August, at the summit of the enlarged Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Eurasian intergovernmental security organization, China again committed to working with other SCO members to expand their renewable energy capacity, and “major platforms” for China-SCO cooperation on energy and green industry were also announced. As President Xi told delegates to the U.N. Secretary General’s climate summit in September, “Green and low carbon transition is the trend of our time.”

The United States, meanwhile, is trying to force its partner countries to buy more U.S. oil and gas. Of the two approaches, global trends favor China. In its latest forecast, the International Energy Agency predicts that the world’s renewable electricity generation will climb to over 17,000 terawatt-hours by 2030, an increase of almost 90 percent from 2023.

With the U.S. actively hostile to climate progress and the E.U. preoccupied with internal divisions and continuing Russian military aggression, climate diplomacy increasingly mirrors the world’s geopolitical shifts. China’s diplomacy among emerging economies has been built on its economic heft; in one recent sign of how far China has come, Xi Jinping was widely described as a “peer competitor” in his meeting with Donald Trump in South Korea last month.

China, India, and Brazil — which represent 40 percent of global emissions — could become the alliance driving U.N. climate diplomacy.

China has also invested years of effort in building alliances through a network of mini- and multi-lateral organizations. These include the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the Forum for China Africa Cooperation, and, importantly for climate negotiations, the BASIC group, the coalition of Brazil, South Africa, India and China that came together in 2009 to promote their collective interests at the Copenhagen COP.

The BASIC group does not align on all issues: India and China are regional rivals, and their unresolved border disputes have regularly resulted in violent clashes. India has an ambitious solar program and is keen to develop its own industry rather than being dependent on China. But recent U.S. diplomatic moves, including high tariffs, Trump’s claim to have resolved the dangerous clash between India and Pakistan in May, and his embrace in June of Pakistan’s army chief, Field Marshal Asim Munir, have pushed India towards China.

At the BRICS summit in Tianjin this year, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping referred to each other as “development partners, not rivals,” and spoke of the need for “mutual respect, mutual interest, and mutual sensitivity.”

The Benban Solar Energy Park in Aswan, Egypt. China helped finance the project as part of its Belt and Road Initiative.Ahmed Gomaa / Xinhua via Getty Images

On climate issues, the interests of the BASIC group align so closely that it seems likely that in the current vacuum of leadership from the rich world, China, India, and Brazil — which collectively represent some 40 percent of global emissions — could become the tripartite alliance that will drive U.N. climate diplomacy, as an editorial in the South China Morning Post in October boldly claimed.

Such a leadership shift would reinforce a trend in climate negotiations toward the interests and priorities of emerging economies that the BASIC group was formed to defend, including the insistence that developed economies must both lead the energy transition and support less developed countries to adapt and to build low-carbon economies.

The three countries differ in approach and capacity: Brazil under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva positions itself as a moral leader, deploying the symbolism and global ecological importance of the Amazon; China’s industrial and technological dominance effectively determines the cost and pace of the world’s energy transition; and India articulates a justice-based claim centred on energy access, equity, and “common but differentiated responsibilities.”

Of the three, China is by far the biggest player in scale of emissions, diplomatic heft, and industrial capacity, and is the driver of the BASIC collaboration. It is also reshaping the world through its pursuit of low-carbon exports, bringing the possibility of global low-carbon development within reach and offering an alternative perspective to energy-hungry emerging economies.

Beijing secured the supply and refining of rare earths, giving China a choke hold over supply chains essential for advanced technologies.

In one illustration of the trend, at a press conference in Beijing in April, COP30 President André Corrêa do Lago highlighted China’s efforts in green development and the role that China’s alliances play in shaping climate diplomacy. “China demonstrates that investing in climate action can bring excellent economic results and improve the lives of its population. This example is crucial for other countries,” he said. “We are discussing climate issues within BRICS… We believe the global South has many of the most important answers to climate change.”

The stakes may be even bigger than the outcome from the negotiating rooms at COP30.

In April 2017, Daniel Gardner, a professor of history at Smith College, published an arresting article on the website of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, headlined “Through climate change denial, we’re ceding global leadership to China.” Donald Trump had announced that the U.S. was leaving the Paris Agreement for the first time, but the U.S. economy in nominal GDP terms was still about 1.6 times larger than China’s, and the U.S. still maintained a convincing technological lead. China’s rapid growth remained dependent on coal, a climate-damaging fuel that China continued to promote as part of its Belt and Road Initiative; its emissions were still climbing rapidly; and the country was not noted as the most cooperative in climate negotiations.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula Da Silva, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, and Chinese President Xi Jinping clasp hands at a 2024 summit of world leaders in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.Wagner Meier / Getty Images

But other trends that attracted less notice were having profound effect: China had all but wiped out the once-leading European solar industry; a subsidiary of a battery company in southern China was developing electric vehicles that would become the world’s leading brand by 2023; 19 new nuclear power plants were under construction; and China was gaining ground in the wind turbine business. To support all this, Beijing had secured the supply and refining of rare earth minerals that others had relinquished to avoid pollution at home, ceding China a virtual choke hold over the supply chains that are essential for every advanced technology.

Today, China’s claim to leadership is hard to challenge. In September, historian Nils Gilman published an article in Foreign Policy that suggested the energy contest between the U.S. and China went far beyond climate politics. “The decarbonization agenda is not simply about reordering markets or industrial policies, but in fact represents the crucible for a new geopolitical order,” he wrote.

Gilman’s argument is that the battle over the substance of global energy is the center of what he calls a “new eco-ideological Cold War” and that, like the last Cold War, this contest over how the world fuels its industrial economies will reshape global alliances. If Gilman is right, and decarbonization is the new geopolitical battleground, China remains confident that the U.S is courting marginalization and that it is China’s leadership and alliances that will matter as the world slowly but irreversibly moves toward a low-carbon future.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!